Like the one-child policy, Beijing’s repressive actions against minority Uighur Muslims are about preserving power.

For years, when I was giving talks or discussing my reporting on China’s one-child policy, well-meaning audience members would inevitably ask a question that I had come to expect: “Of course forced abortions and sterilizations are bad,” they would say, “but isn’t the one-child policy good, in some ways? Doesn’t it help lift millions of people out of poverty?”

This has always been the Chinese Communist Party’s narrative. The one-child policy, it claimed, was a difficult but necessary move that was crucial for the country’s advancement. Deng Xiaoping, then China’s paramount leader, insisted in 1979 that without a drastic fall in birth rates, “we will not be able to develop our economy and raise the living standards of our people.”

Recent reports from theAssociated Press and the noted Xinjiang scholar Adrian Zenz about forced sterilizations imposed on China’s repressed Uighur minority should quash this lingering, pernicious fig leaf. If the one-child policy was designed to boost economic growth and benefit citizens, why is Beijing actively suppressing reproduction among Uighurs—who are Chinese citizens—when the country’s birth rate has plunged to its lowest in 70 years, imperiling future growth? Why is the party telling Han Chinese to have more children, even as it sterilizes more Uighur women than the population of Hoboken, New Jersey?

The answer, of course, is that China’s birth-control policies have always been less about births, and more about control. Those who drafted the one-child policy were cynically more concerned with the preservation of power than helping lift people out of poverty. That’s why China’s leaders long resisted calls to end the policy, even though economists had persistently warned that it was shrinking China’s workforce, diminishing productivity, and storing up a future problem in pension shortfalls. The alternative would’ve meant giving up a powerful tool for social control (as well as one that reliably generated at least $3 billion annually in fines for violations, by Beijing’s own admission).

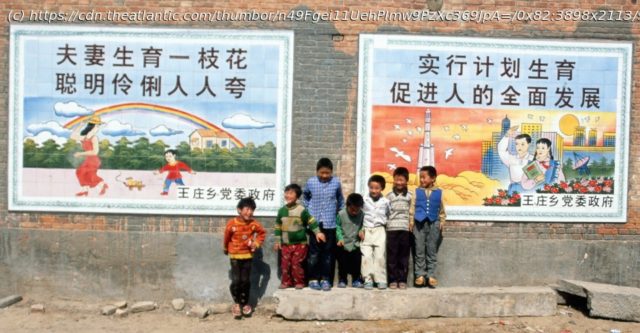

I know this because I covered China’s economic miracle as a correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, and spent years researching and writing an award-winning book examining the costs and consequences of the world’s most radical social experiment, which began in 1980 and tapered in 2016, when Beijing increased the number of children a family could have to two. In my quest to understand how the state policed the womb, I heard many chilling stories: I spoke with women forced to have abortions as late in their pregnancy as seven months; officials who described how they cornered and chased pregnant women like prey, and mothers who recounted heartbreaking acts of abandonment and infanticide. The bulk of these stories, though not all, involved the country’s majority Han population, who were subject to more stringent restrictions than China’s ethnic minorities, including its Uighur population.

Now the scales have tipped.