Scholar Michael Sawyer brings the political philosophy of Malcolm X to bear on the horrors taking place in Gaza.

In deep times of sorrow and catastrophe, some of us flee. We flee either because we don’t want to face the weight and ugliness of the horror — willed ignorance — or we flee because we need a reprieve. I find myself needing a reprieve, though I’m by no means beyond the trappings of the former. There are other times when I seek out the wisdom of those human beings who refused to turn their faces from forms of social terror and found strength to endure. Think here of Ida B. Wells-Barnett and her powerful fight against the lynching of Black people as forms of white, twisted desire and an attempt to control Black freedom.

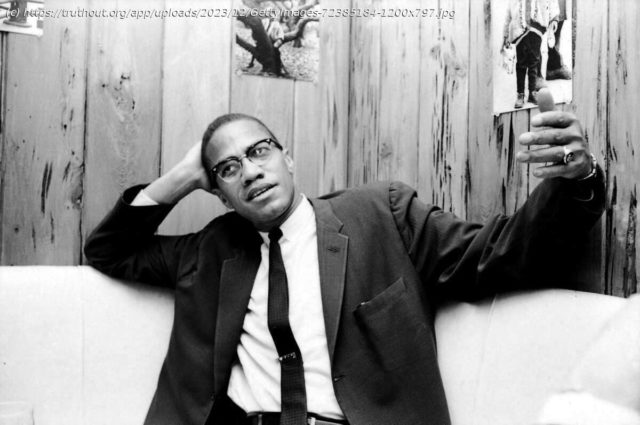

I recall as a teenager lying back on the floor listening to Malcolm X speeches on vinyl records that my father had collected. Malcolm X’s powerful and articulate voice encouraged me to read the dictionary, to embody the sting of his discourse, the truth that he spoke. I wanted to be like Malcolm X. I didn’t want to be a milquetoast person afraid to speak the truth. Many years later, I would read as much as I could get my hands on by and about Malcolm X. I found that many people were more interested in donning the X as opposed to understanding the complexity of the man. In 1991, I had the good fortune to meet Malcolm’s wife, Betty Shabazz, who also happily signed my copy of The Autobiography of Malcolm X. I also had the deep honor of meeting Malcolm’s youngest brother, Robert Little, in 1993. He and I spent deep quality time discussing Malcolm.

As I was thinking about the horrors taking place in Gaza, the Black Lives Matter movement, and so much more, I thought of Malcolm, his wisdom and his indefatigable courage. Wondering what Malcolm thought about the crucible of this moment, while understanding the potential mistakes involved in presentism, or where we judge the past using dominant attitudes from the present, I turned to scholar Michael Sawyer. Sawyer is an associate professor of African American Literature and Culture, a faculty affiliate of Africana Studies and the Director of Graduate Studies of the Department of English at the University of Pittsburgh, as well as the author of the groundbreaking book, Black Minded: The Political Philosophy of Malcolm X. We discussed what Malcolm X means to us today and why his thought continues to be powerfully germane. The interview that follows has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

George Yancy: When I say the name of Malcolm X (who later took the name El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) in the context of the college classroom, I find that many students mistakenly associate him with advocacy for wanton violence. But in Malcolm X Speaks (edited by George Breitman), Malcolm X is clear about how he understands violence. He says, “I have never advocated any violence. I have only said that Black people who are the victims of organized violence perpetrated upon us by the Klan, the Citizens’ Councils, and many other forms, should defend ourselves. And when I say we should defend ourselves against the violence of others, they use their press skillfully to make the world think that I am calling for violence, period.” Black self-defense — to take a stand against Black brutalization and oppression — for Malcolm X, is not the same as white terrorism, which is predicated upon the hatred of Black people, their dehumanization and disposability. Malcolm X reminds me of the distinction made between terrorism and the collective struggle against oppression maintained by the Palestinian American activist and scholar Edward Said.

Said is clear that terrorism or the emphasis on armed struggle that is indiscriminate and “sometimes foolishly and in a political sense stupidly relied on” is unacceptable. Said would not accept the killing of innocent civilians. But he was supportive of the struggle against oppression. It is not lost on me that Patrick Henry, who was one of the “founding fathers” of the United States and a famous orator, was against the hegemonic British rule over the American colonies. Indeed, he is known as saying, “Give me liberty, or give me death!” I imagine that the Black people that he enslaved would have been killed had they made such a fiery and insurrectionist claim against slavery and their so-called white masters. That brings me to my main question. Black people continue to live under conditions of anti-Black racism. Yet, when we resist, we are seen as violent. We can’t fight against anti-Blackness in the name of liberty where this might mean deciding to die in the process.

Talk about how Malcolm X would frame the contradictions that I’m suggesting. How might he propose that we collectively think about resisting anti-Black racism in the U.S. in the 21st century? And how might he propose Black people support other collective groups that have been negatively racialized and othered under colonial and oppressive conditions? I’m thinking here specifically of Palestinians. Malcolm X was critical of the dispossession of Palestinians, writing: “Did the Zionists have the legal or moral right to invade Arab Palestine, uproot its Arab citizens from their homes and seize all Arab property for themselves just based on the ‘religious’ claim that their forefathers lived there thousands of years ago? Only a thousand years ago the Moors lived in Spain. Would this give the Moors the legal and moral right to invade the Iberian Peninsula, drive out its Spanish citizens, and then set up a Moroccan nation where Spain used to be, as the European Zionists have done to our Arab brothers and sisters in Palestine?”

Michael E. Sawyer: First, George, I want to thank you for the opportunity to be in dialogue with you on this platform, especially as we prepare for the 100th anniversary of the birth of Malcolm X on May 19, 2024. The thrust of your question is timely and provocative in that it deals with the unspeakable violence we are all witness to in the conflict between Israel and putatively Hamas. I say putatively because the carnage we have witnessed is, in toto, skewed towards those we understand to be non-combatants. As we situate ourselves to deal with this question through the thinking of Malcolm X, we will have to develop some abstract understandings of several terms: violence vs. nonviolence, resistance, and something that approximates the right (or perhaps the necessity) to resist regimes of oppression, whether they be state-sanctioned or not.

Abstractly, Malcolm X insists upon a very careful, what I will call a “distinct-indistinction,” between violence and nonviolence as forms of resistance on the part of oppressed subjects. Broadly, he forces us to realize that as far as systems of power are concerned, any activity that is designed to destabilize structures of power are deemed “violent.” Meaning that all technologies of resistance — say, for instance, speech acts against a regime — are reacted to, or at least categorized, in the same manner as an armed insurgency. This means that as a practical matter, the telos [or end goal] of any form of protest — let’s use the term “disruptive activity” — will almost universally first be characterized as violent and then reacted to in violent fashion. That is, the abstraction I referenced above that needs to be further glossed as also distinct from acts of self-defense against violence which Malcolm X understands as required to be violent. That abstraction allows us to deal with the specificity of your question that I take to situate, and I believe this to be correct, the plight of Palestinians as inextricably related to the denial of liberty to Black people in this country.

That linkage is, in my estimation, one of the foundational advances provided by the philosophical system (if you will allow me that) Malcolm X developed in that he understands “Black” to reference aggrieved subjects wherever and whoever they might be; a form of global transnational and trans-subjective Blackness. What that means, returning to the abstraction developed above, is that resistance to the occupation of Gaza or the West Bank by anyone will necessarily be seen as violent by the state of Israel. And I want to take care to acknowledge that there are actors within that government who do not subscribe to this view, and are reacted to violently. That means that a terror attack like that on October 7 by Hamas and others will be understood as a kind of capstone in a logic of violence, whether individual acts in that chain of events can be characterized as violent or not.

What this seems to assert is that the answer to the totality of your question regarding what is to be done to effectively oppose systems of state-sanctioned oppression is to mount a structural/systemic response to the structural/systemic refraction of all protest into acts of violence that necessarily tend to blur and, at the same time, magnify actual acts of violence. What Malcolm X endeavors to do through his transnational and trans-subjective understanding of Black(ness) was to create a type of super-citizenship that enjoyed the protection of recognized states for those situated within crucibles of oppression wherever that might be. This becomes Black Panther Party orthodoxy in that oppressed African Americans were deemed to be substantively existing in colonies and therefore colonized. Here, “super” is in great measure meant to be something like “greater than” but also shorthand for “superseding” in that it is an overarching understanding that invalidates typologies of citizenship that are designed only to render subjects objects in terms of the law: acted upon rather than protected by.