We’ve entered a new phase in the history of whole genome sequencing (WGS). Consider that researchers at University of Toronto just launched a massive project to sequence the whole genomes of 10,000 people per year. This is truly astounding when you recall that it took 13 years and $3 billion to sequence the first human genome, and that as recently as 2012 there were only 69 whole human genomes that had ever been sequenced.

We’ve entered a new phase in the history of whole genome sequencing (WGS). Consider that researchers at University of Toronto just launched a massive project to sequence the whole genomes of 10,000 people per year. This is truly astounding when you recall that it took 13 years and $3 billion to sequence the first human genome, and that as recently as 2012 there were only 69 whole human genomes that had ever been sequenced.

We’ve been using WGS to personalize medicine since 2010, when WGS was first used to inform the treatment of a patient .

Now, as our public and private reference databases grow and we have access to more genomic data than ever, we’ll begin to rely heavily on machine learning to realize the full potential of WGS. Increased access to machine-learning capabilities and processing power is fueling not only genetic research but also the broad application of genomics across a number of industries. We’re just beginning to see cutting-edge WGS technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) leveraged in other industries like agriculture and food safety.

To better understand the importance of WGS as an applied science and to better imagine how WGS will rapidly transform a variety of industries in the next few years — especially as we combine it with technical treatments like machine learning — it’s helpful to understand how fundamental processes of sequencing and analysis have evolved over time.

It’s become commonplace to associate WGS with the study of human DNA, but of course, WGS is a laboratory process that can be used to reveal the complete DNA sequence of any organism. The first organism to have its whole genome sequenced was, in fact, Haemophilus influenzae , a bacterium that resides in the human respiratory tract. This breakthrough came in 1995. It wasn’t until 2000, a full five years later, when researchers sequenced the whole genome of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster.

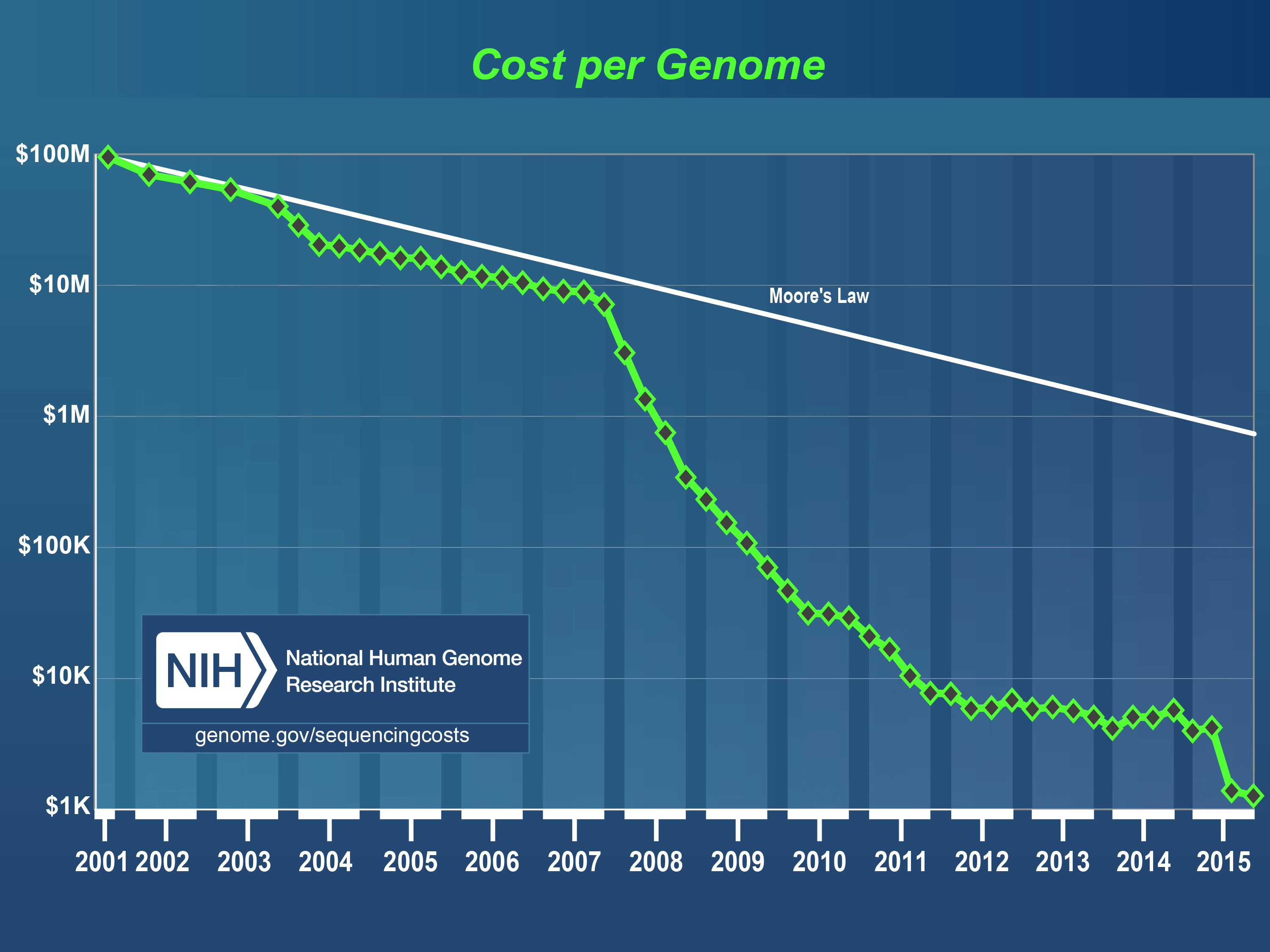

Just three years passed before the Human Genome Project published the whole sequence of a human genome in 2003. This momentous breakthrough — among the most important in the history of science — required a 13-year-long Herculean effort that cost approximately $3 billion dollars.

The commercial viability of WGS remained very much in doubt until the introduction of next-generation sequencing (NGS) in 2005. NGS is something of a catch-all term describing a variety of sequencing technologies that have largely replaced Sanger sequencing.

These technologies, developed at Illumina, Roche, Life Technologies and a number of other firms, have greatly reduced the time and cost of DNA and RNA sequencing, revolutionizing both the study and application of genomics and molecular biology. For the last year or so, we’ve been on the verge of achieving the $1,000 whole human genome. In fact, Veritas Genetics has been hailed as the first company to be able to sequence, analyze and interpret the human genome for less than $1,000.

The $1,000 figure has always been an arbitrary goal, of course. What really matters is that we can now sequence the human genome quickly and affordably to build the massive reference databases researchers need, like the one being built at University of Toronto, to better understand complex diseases, how genes interact with each other and how genes respond to environmental changes.