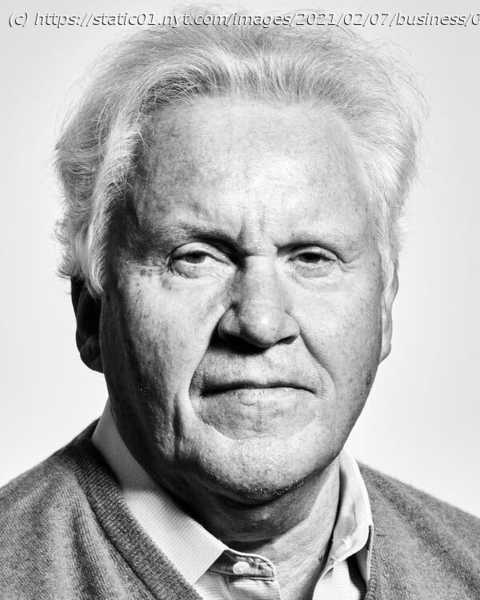

The C.E.O. who followed Jack Welch tried, and failed, to revive the company’s stock price. He’s owning up to some of his mistakes now — and assigning some blame.

There are two ways to think about Jeff Immelt’s 16-year run as chief executive of General Electric. The charitable interpretation is that Mr. Immelt was dealt an impossible hand. He followed the two-decade reign of Jack Welch, during which G.E. became the most valuable company in the world. His second day on the job was Sept.11,2001, and fallout from the terrorist attacks left several of G.E.’s major business lines battered. And G.E. Capital, which Mr. Welch built into what was essentially a giant unregulated bank, was a ticking time bomb that almost blew up during the financial crisis. The less charitable interpretation is that Mr. Immelt bears singular responsibility for allowing G.E. to fall apart. Mr. Immelt paid too much for some acquisitions and didn’t get enough for some divestitures. Rather than rein in G.E. Capital, he let it spin out of control. And critics contend he was set in his ways, misguided in his big bets and unable to adapt to changing market conditions. Either way, the results were disastrous. On Mr. Immelt’s watch, G.E. stock plunged some 30 percent, wiping out more than $150 billion in market value and obliterating the savings of thousands of G.E. retirees. Since Mr. Immelt was pushed out in 2017, it has only gotten worse. G.E. was dropped from the Dow Jones industrial average, its stock has continued to slide and it recently paid $200 million to settle with the Securities and Exchange Commission for misleading investors. Once a paragon of modern management excellence, G.E. became a punchline. It was a stunning fall for a company that was among the country’s most admired corporations for a century, popularizing everything from the light bulb to the refrigerator, mass-producing televisions and washing machines, and ushering in the modern age with jet engines, power plants and plastics used during the moon landing. Today G.E. still makes engines, wind turbines and medical equipment, and Mr. Immelt did generate some organic growth. Gone, however, are its once-vaunted businesses in appliances, plastics, locomotives, light bulbs, media and more. It is an object lesson in how even the mightiest companies can fall victim to bad management, black swan events and the unforgiving nature of the stock market. Dueling narratives have now emerged that try to explain what went wrong. In “Lights Out,” two Wall Street Journal reporters lay the blame squarely at the feet of Mr. Immelt, describing in detail how his rosy projections were too often out of step with reality. Mr. Immelt,64, is telling his side of the story in “Hot Seat,” a book in which the former C.E.O. seeks to own up to his failures while explaining the complexities of running a company with more than 200,000 employees and operations around the globe. Mr. Immelt acknowledges that he made mistakes, and writes candidly about his tactical errors and lapses in judgment. But there often seems to be a caveat, something to explain why it wasn’t all his fault: He was working with the best information he had. McKinsey had done a study. Goldman Sachs had offered its assurances. The markets moved in unpredictable ways. For the most part, Mr. Immelt does not blame other individuals for his missteps — with one major exception. In his final years as C.E.O., Mr. Immelt writes that Steve Bolze, the head of G.E.’s power division, essentially ran one of G.E.’s most important businesses into the ground. Mr. Bolze championed the ill-fated acquisition of Alstom, a French energy company, then froze when it came time to execute the deal. He “wasn’t committed,” and “lacked what I can only describe as a C.E.O.’s intuition,” Mr. Immelt writes. He was “naïve,” “didn’t have command of the most basic material,” was “indecisive,” was “not operationally sharp” and “didn’t seem to be thinking ahead.” At the same time, Mr. Immelt writes, Mr. Bolze engaged in “unyielding politicking” and launched an overt campaign to replace Mr. Immelt as C.E.O., while abandoning his day-to-day operational duties. “His main concern seemed to be self-promotion,” Mr. Immelt writes, and “his behavior had become self-serving to the point of outrageous.” Not firing Mr. Bolze, Mr. Immelt writes, was “a terrible mistake, maybe the worst I ever made.” (“Many clearly have different perspectives on this chapter in G.E.’s history,” Mr. Bolze, now an executive at Blackstone, said in a statement. “Jeff’s narrative simply doesn’t align with the facts.”) The leaders who replaced Mr. Immelt don’t fare much better in the book. John Flannery, who took over for Mr. Immelt, “created a culture defined more by victimhood than by a sense of purpose.” That came as no surprise to Mr. Immelt. “Flannery couldn’t make a decision,” Mr. Immelt writes. “He was ponderous and always needed reams of data before choosing a course of action.” Mr. Immelt, who received more than $200 million in compensation during his time at G.