Venus is almost the same size, mass and density as Earth. So it should be generating heat in its interior (by the decay of radioactive elements) at much the same rate as the Earth does. On Earth, one of the main ways in which this heat leaks out is via volcanic eruptions. During an average year, at least 50 volcanoes erupt.

Venus is almost the same size, mass and density as Earth. So it should be generating heat in its interior (by the decay of radioactive elements) at much the same rate as the Earth does. On Earth, one of the main ways in which this heat leaks out is via volcanic eruptions. During an average year, at least 50 volcanoes erupt.

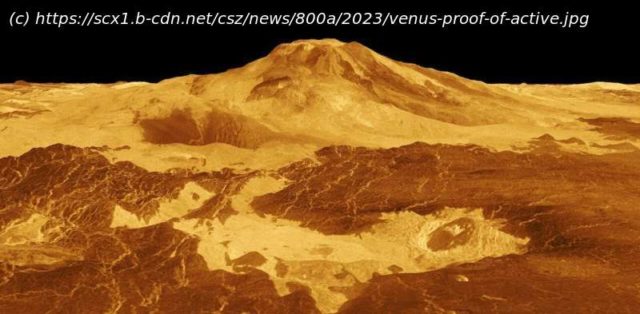

But despite decades of looking, we’ve not seen clear signs of volcanic eruptions on Venus—until now. A new study by geophysicist Robert Herrick of the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, which he reported this week at the Lunar & Planetary Science Conference in Houston and published in the journal Science, has at last caught one of the planet’s volcanoes in the act.

It’s not straightforward to study Venus’s surface because it has a dense atmosphere including an unbroken cloud layer at a height of 45-65km that is opaque to most wavelengths of radiation, including visible light. The only way to get a detailed view of the ground from above the clouds is by radar directed downward from an orbiting spacecraft.

A technique known as aperture synthesis is used to build up an image of the surface. This combines the varying strength of the radar echos bounced back from the ground—including the time delay between transmission and receipt, plus slight shifts in frequency corresponding to whether the spacecraft is getting closer to or further from the origin of a particular echo. The resulting image looks rather like a black and white photograph, except that the brighter areas usually correspond to rougher surfaces and the darker areas to smoother surfaces.