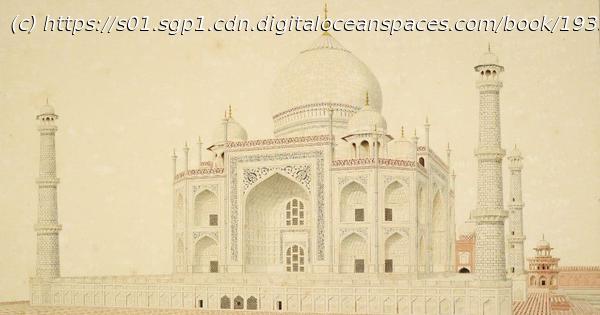

Illustrations commissioned by Lady Maria Nugent reveal a careful understanding of Mughal architecture and ornamentation.

We might think that an album measuring a metre in length would be a cumbersome thing to travel with, but it would probably be made less difficult if you had “100 boats, 87 elephants, 355 camels, 1,033 bullocks, and more than 3,000 attendants” to assist you. Lady Maria Nugent (1771-1834) owned an album that contained 25 beautifully illustrated drawings of the Taj Mahal and surrounding buildings in Agra and which is now in the British Library.

On visiting Agra in 1812, she stated her intent to commission the set, ‘‘I mean to have drawings of every thing – the beautiful Taaje in particular”. Many of the drawings were folded to fit inside the original album. For conservation reasons, the album was unbound and the drawings were flattened and individually mounted.

In 1812, Lady Maria Nugent undertook a tour across northern India, surrounded by the retinue mentioned above. She was accompanying her husband, Sir George Nugent (1757-1849), who had been appointed commander-in-chief by the East India Company in 1811. While in post, his yearly salary totalled £20,000, amounting to the second highest-paying position in the British Empire at the time.

Lady Nugent was not a novice traveller; she had previously lived in Jamaica, where her husband served as governor from 1801 to 1806. She is known primarily for the travel writings she penned during these voyages, especially those documenting her stay in Jamaica, which have been critically studied for her views on race, gender and slavery.

While in India, Lady Nugent amassed a huge collection of art. It would seem, however, that one of her acquaintances was not impressed by the drawings she commissioned of the Taj Mahal. In a letter to her close friend Lady Temple, Lady Nugent writes “I had a letter from her [Lady Hood] today dated Agra. She is delighted with that Place and bids me burn my Drawings of the Taje as no pencil can ever represent anything half so beautiful”.

Notwithstanding Lady Hood’s assessment, the drawings reveal a careful understanding of both the architecture and ornamentation of Mughal buildings. The watercolour of the mausoleum of I’timad al-Daula meticulously records the intricate marble screens and colourful inlay work found on the outer walls of the building. Despite their level of detail, the works might not have been drawn from direct observation.

As art historian JP Losty notes, Indian artists often worked from existing drawings; he suggests one or two artists would have drawn the buildings from life, likely creating multiple copies, with following artists working from these earlier examples. Although many architectural drawings of Agra have survived, the names of very few artists working in this genre are known today, the most celebrated being Latif (fl.