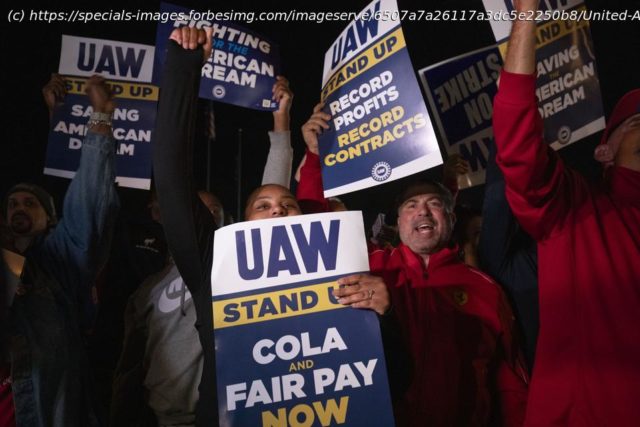

The UAW strike reveals tension between climate goals and union jobs. Just transition is needed in climate-exposed sectors including fossil-fuel producing and using ones.

the United Auto Workers (UAW), which represents employees of GM (General Motors), Ford, and Stellantis (that owns Jeep, Ram, Chrysler, Dodge, and Fiat brands), went on strike. Apart from its implications for the auto industry and U.S. Presidential politics, this strike points to contradictions in the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) approach to running the modern firm. Why so?

In the 21st century, some might say that businesses are transformed because they do not focus solely on maximizing shareholder wealth. Contrary to the so-called Friedman doctrine, businesses are embracing climate issues, adopting transparent governance practices, recognizing their social obligations, and treating their labor force and communities with respect. This transformation has a descriptor: ESG.

The “Detroit Three” are supposed to be ESG role models. General Motors (GM) prides itself as an ESG leader and a climate champion. Its emission targets are verified by the Science-Based Targets initiative. GM has even asked its suppliers to sign an ESG pledge where “suppliers commit to achieving carbon neutrality for Scope 1 and 2 emissions and confirm they have advanced management systems in place for labor and human rights, ethics and sustainable procurement practices through a third-party assessment by EcoVadis.”

Ford Motor Company is also an ESG leader. It has extensive involvement with the CDP (formerly Caron Disclosure Project), and the UN Sustainability Development Goals. It has adopted a sustainability financing framework, which “covers funding of environmental and social projects … and guides how projects are evaluated, selected, managed, and reported.”

Stellantis prides itself as an ESG leader as well. It publishes an annual corporate social responsibility (CSR) report. It has identified six CSR macro-risks and addresses them following the UN Sustainable Development Goals guidelines. It wants to achieve carbon net-zero emissions by 2038.

So, why are these ESG leaders facing a strike, and what does this episode tell us about ESG’s problems?

ESG as the new and improved CSR

In a commentary co-authored with Jennifer Griffin, we made the argument that ESG is the old CSR wine in a new bottle. The reason is that both offer very similar guidelines on how corporations should think about their economic and social purposes.

Howard Bowen’s 1953 book, Social Responsibilities of the Businessman launched the CSR movement. Thus, this movement emerged during the cold war, with vigorous debates on merits of capitalism and socialism. The hope was that as the social welfare state and the New Deal changed the nature of the government, CSR would change the nature and purpose of the corporation.

CSR outlived the cold war and got a second life as the failings of the so-called “Washington Consensus” became evident and the backlash against globalization gathered speed (remember the 1999 Seattle riots at the World Trade Organization meeting). In 2000, Kofi Annan, the United Nations Secretary-General, announced the Global Compact, an attempt to translate CSR into an actionable global program.

CSR in general and even programs such as the Global Compact lack a verifiable metric. ESG corrects this by outlining how to assess companies’ social and environmental activities, along with governance transparency.