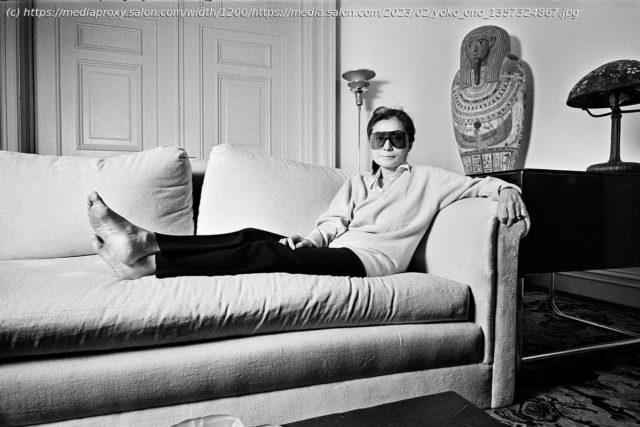

As an artist and collaborator, Yoko Ono, who turns 90 today, has always been ahead of her time

Today is Yoko Ono’s 90th birthday. Since the late 1960s, John Lennon’s widow has served as a lightning rod for the ire of an overly large coterie of Beatles fans who would come to blame her for the group’s disbandment. In many ways, this rabid disgust can be attributed to unchecked misogyny, even racism, whose animus can be traced to an abiding disbelief by certain fans that Lennon could actually love someone like Ono, preferring to believe, it seemed, that she had somehow beguiled him.

In September 1980, during the final weeks of his life, Lennon confronted this issue, admitting his frustration to journalist David Sheff. “Anybody who claims to have some interest in me as an individual artist, or even as part of the Beatles,” he remarked, “has absolutely misunderstood everything I ever said if they can’t see why I’m with Yoko. And if they can’t see that, they don’t see anything.” Incredibly, not even Ono’s unfathomable trauma at having witnessed her husband’s senseless murder would quell the naysayers and detractors who disparage her name.

As we celebrate Ono’s ascent into the ranks of the nonagenarians, we can perhaps more profitably honor her aesthetic contributions by ignoring her detractors and highlighting her artistry. By the time that she met Lennon in 1966, Ono had successfully established herself amongst the Dadaesque group of artists known as Fluxus (from the Latin word “to flow”).

Ono had begun exhibiting her performance art in such works as “Cut Piece,” in which she reclined onstage while audience members cut off her clothing with a pair of scissors until she was naked. During the summer of 1966, Ono left New York in order to attend the “Destruction in Art Symposium,” an international congress that Fluxus was hosting in London. Before long, she took to hanging out with the gaggle of hipsters who frequented the Indica Gallery.