Despite efforts across the globe to move toward a circular plastics economy, more than three quarters of the 400 metric tons of plastic produced worldwide each year still ends up as waste.

Despite efforts across the globe to move toward a circular plastics economy, more than three quarters of the 400 metric tons of plastic produced worldwide each year still ends up as waste.

A group of researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign demonstrated a way to use the renewable energy source of electricity to recycle a form of plastic that’s growing in use but more challenging to recycle than other popular forms of plastic.

In their study recently published in Nature Communications, they share their innovative process that shows the potential for harnessing renewable energy sources in the shift toward a circular plastics economy.

“We wanted to demonstrate this concept of bringing together renewable energy and a circular plastic economy,” said Yuting Zhou, a postdoctoral associate and co-author, who worked on this groundbreaking research with two professors in chemistry at Illinois, polymer expert Jeffrey Moore and electrochemistry expert Joaquín Rodríguez-López.

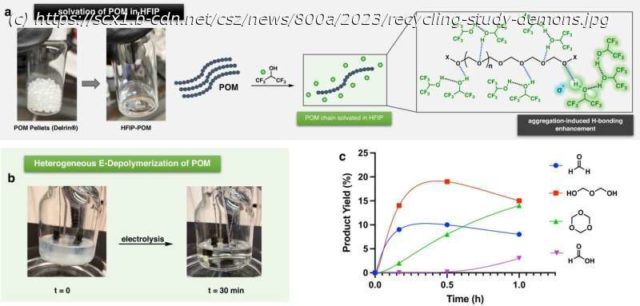

The project was conceived by Moore who had experience working with Poly(phthalaldehyde), a form of polyacetal. Polyoxymethylene (POM), a high-performance acetal resin that is used in a variety of industries, including automobiles and electronics. A thermoplastic, it can be shaped and molded when heated and hardens upon cooling with a high degree of strength and rigidity, making it an attractive lighter alternative to metal in some applications, like mechanical gears in automobiles. It is produced by various chemical firms with slightly different formulas and names, including Delrin by DuPont.

When recycling, those highly crystalline properties of POM make it difficult to break down.