Ask Clemson’s star what he wants more than anything, and it’s a simple answer: to beat Notre Dame. But that’s not the whole picture. What he has done in 2020 is to sketch out a broader vision for his life.

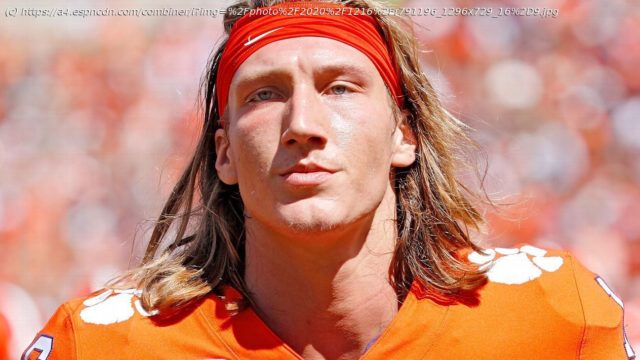

People keep asking how Clemson quarterback Trevor Lawrence has changed in 2020. They ask because, on the surface, it’s tough to see, but logic suggests there must be a reason the likely future No.1 NFL draft choice is still playing college football, and the assumption is, he’s refining some small flaw in his otherwise exceptional game, polishing the already shimmering diamond to perfection. So people ask, again and again, what’s changed? They ask Tigers coach Dabo Swinney, and he goes on about leadership and Lawrence’s ability to ensconce himself into every nook and cranny of the Clemson locker room. But, of course, Lawrence also won a national championship as a true freshman, just 11 starts into his college career, so this answer feels less about genuine growth than simple experience. So they keep asking. They ask Lawrence’s teammates. This season’s receiving corps has been a sparsely stocked cupboard compared with the overflowing riches Lawrence enjoyed his first two seasons at Clemson, and yet the stat line still looks gaudy. Ask Amari Rodgers, the team’s most reliable threat through the air, and he’ll rave about how far Lawrence has taken this group, because every receiver gets a little better when the best QB in the country is throwing him the ball. And this season, Lawrence is fitting passes into even tighter windows than before. Still, it’s hard to imagine Lawrence did all this — the decision to play, the fight for player empowerment, the frustrating recovery from COVID-19 — all to fit a pass into a window an inch smaller than last season. And so they keep asking. They ask Lawrence himself, and he’s got plenty of stock replies. He’s got the playbook down pat. He’s making faster reads. He’s more accurate and consistent. But it feels hollow to simply say he’s a little better at all those things he was already better at than nearly anyone else on the planet. In another year, there’d be less need for these questions. Lawrence, a junior, was, in the mind of so many scouts, ready for the NFL from day one as a freshman, but the rules meant he’d be at Clemson for three seasons. But this is 2020, and the rules don’t exactly apply. Plenty of guys with just a shred of his talent, players who don’t approach the “sure thing” label Lawrence has had since high school, chose to opt out and avoid the stringent COVID-19 protocols. Not Lawrence, though. He wanted to play. And now, he leads No.3 Clemson into the ACC championship game against No.2 Notre Dame (Saturday,4 p.m. ET on ABC), with a victory basically assuring a spot in the College Football Playoff. Lawrence didn’t just want to play, he demanded to play. He helped start a movement, working with teammates and friends from across college football, begging the powers that be to consider what the players wanted, to give them a chance to make a season work amid a global pandemic. Lawrence wasn’t the architect of the movement, but his signature on the “We Want to Play” request stood out and forced others to take notice. So if the most famous, most refined, most pro-ready player in college football wanted to play, if the guy with virtually nothing to gain and so much to lose insisted on a 2020 season, surely there was a reason. The short answer is that Lawrence is a devout competitor. The need to compete burns deep in his soul, and to sit out a season would be hell. Saturday’s rematch against Notre Dame looms large for Lawrence because it’s a win his team needs to add a sixth consecutive ACC championship to the trophy case and, in doing so, set the Tigers on a path toward another national title. More than that, though, it’s an opportunity for Lawrence to exorcise one of the few regrets in his career — that he missed Clemson’s first matchup with the Fighting Irish last month while recovering from COVID-19, possibly losing his shot at a Heisman Trophy in the process. “He loves playing,” Rodgers said. “It tore him up [that] he missed those games, especially Notre Dame.” In high school, Lawrence once told his coach his ultimate goal was to become the best quarterback of all time, but he’s evolved in his thinking. He still wants to be better than Peyton Manning or Tom Brady, but it won’t be enough to simply do what they did, only better. He wants to blaze a different path and define greatness in his own way. “You look at a lot of the guys in the NFL, it seems like it is their whole life, where every minute of the day is dedicated to football,” Lawrence once said, months before his sophomore season began. “And I don’t want that to be me.” And maybe that’s not exactly why Lawrence is still here, but it at least feels like a worthy explanation. “I don’t think you can overstate what he’s meant to college football this year,” Swinney said. “He’s used his platform to change the whole narrative.” Less than a week after COVID-19 shut down the sports world in March, Lawrence and his girlfriend, Marissa Mowry, launched a GoFundMe to help people most impacted by the virus. Almost immediately, Clemson’s compliance department nixed the plan, suggesting it was a potential violation of the NCAA’s ban on athletes using their name, image and likeness for crowdfunding. And that might’ve been the end of it, except this was one of the most famous players in college football, and the media had already taken notice of the charitable gesture. Suddenly the pressure was on the sport to change the rule — or at least interpret it a bit more loosely. Within days, Clemson backed down, and Lawrence and Mowry relaunched a new-and-improved donation site. Then in June, as protests erupted across the country in the wake of George Floyd’s death while in police custody, athletes began to speak out about racism, police brutality and social justice. Players had done this before, of course, but rarely did the message resonate to the furthest reaches of any given fan base without getting lost in (or quieted by) the status quo. Lawrence had been talking about all of this with his pal Darien Rencher, a Black backup running back who had become one of the QB’s most trusted confidants. The two sat in an apartment in Atlanta, watching smoke billow from a protest, and Rencher explained why he hurt, why so many people who look like him hurt, and why protesters were now insisting the rest of the world feel their pain, too.