Probably.

Louisiana enacted legislation requiring every public school in the state to display a specific version of the Ten Commandments in each classroom. “I can’t wait to be sued,” Republican Gov. Jeff Landry proclaimed a few days before signing the new law, erasing any doubt that the purpose of this legislation is to coax the Supreme Court into legalizing religious displays in government-run classrooms.

But will he get away with it?

The answer is unclear, and the Court’s current First Amendment precedents cut strongly against Louisiana’s law. But the Court’s GOP-appointed majority has also spent the last several years rolling back precedents separating church and state, so there is a very real risk that they will allow public schools to promote Christianity.

Get the latest developments on the US Supreme Court from senior correspondent Ian Millhiser.

The Court has historically held that public schools have an unusually high obligation not to promote religious viewpoints, in large part because the young people educated in those schools are unusually vulnerable to coercion. Allowing this law to stand would mean taking a sledgehammer to the wall separating church and state.

Indeed, the new state law appears to be written to be maximally offensive to the Constitution, or, at least, the Constitution as it was understood before former President Donald Trump remade the Supreme Court.

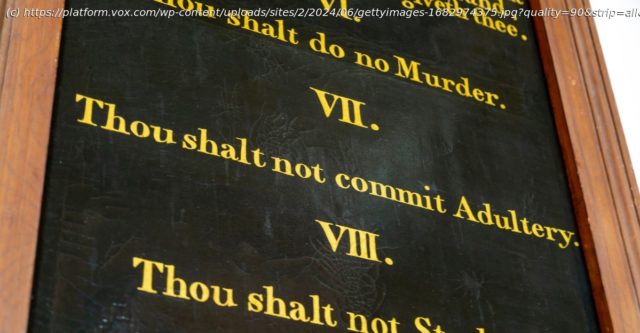

The Court, for example, has often permitted the Ten Commandments to be displayed in government buildings when it is shown alongside other historical documents that do not convey a religious meaning. The Supreme Court’s own courtroom, for example, displays Moses holding the Ten Commandments alongside 17 other images of mostly secular lawgivers — thus indicating that the Commandments are displayed not as an endorsement of a particular religious belief but merely as one of many examples of famous legal codes.

But Louisiana’s law mandates that only the Ten Commandments must be displayed in classrooms. Many classrooms are likely to display them in isolation, since they are the only document that must be visible to students under the law — although the law does permit the Commandments to be displayed alongside three other documents.

Similarly, in Engel v. Vitale (1962), a seminal case prohibiting government-mandated prayers in school, the Court specifically warned against repeating the English Parliament’s practice of setting out “in minute detail the accepted form and content of prayer and other religious ceremonies to be used in the established, tax-supported Church of England.” Under Engel, a law that requires the government to use very specific words when it communicates a religious view is particularly offensive to the Constitution.

But Louisiana’s law does not just require classrooms to display the Ten Commandments. It also lays out in minute detail the specific wording that display must use, requiring classrooms to use a version of the Commandments that is often used by Protestants and that is different than the version preferred by most Catholics and Jews.

The law, in other words, appears to have been drafted to undercut as much of the Court’s precedents separating church from state as possible. To uphold this law in its entirety, the Supreme Court will need to burn nearly all that remains of the Constitution’s ban on laws “respecting an establishment of religion” to the ground.

And it seems eminently possible, in light of the Court’s most recent religion decisions, that a majority of the justices will light that fire with enthusiasm.

Until very recently, there was no question that states could not require public schools to display religious iconography such as the Ten Commandments, at least when that iconography was displayed in order to advance a religious viewpoint. That was the holding of Stone v. Graham(1980), a Supreme Court decision striking down a Kentucky Ten Commandments law similar to Louisiana’s new law.

But Stone was rooted in the Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Lemon v.

Home

United States

USA — Financial Louisiana wants the Ten Commandments in public schools. Will the Supreme Court...