If we want to research a subject, how do we do it? We could read about it in books or do experiments in a lab. Or another way is to find people who know something about it and ask them.

If we want to research a subject, how do we do it? We could read about it in books or do experiments in a lab. Or another way is to find people who know something about it and ask them.

Collecting information from members of the public has long been a method of scientific research. We call it “citizen science”. According to National Geographic, this is “the practice of public participation and collaboration in scientific research to increase scientific knowledge.”

Today, citizen science is a popular practice, with dozens of programs designed by academics to engage the public and leverage power by numbers. Its origins, however, go much farther back than you might think—all the way to ancient times.

Most of us know of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) for his philosophical works, but he was also a great scientist.

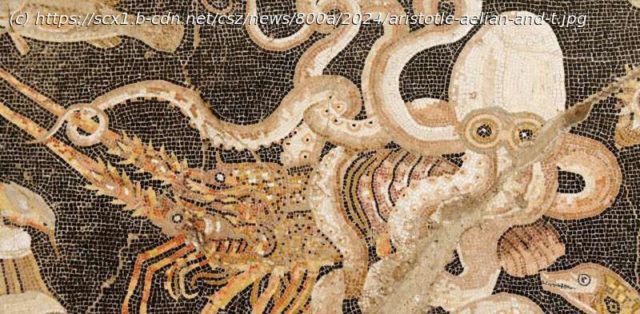

Aristotle consulted the general public when undertaking his scientific research projects. He wrote a number of books about animals, the greatest of which was his “History of Animals”. He also wrote smaller works, including Parts of Animals and Generation of Animals. Collectively, these are usually referred to as Aristotle’s biological writings.

The Roman scholar Pliny the Elder (approximately 24–79 CE) has told us about some of Aristotle’s research methods when writing these texts.

According to Pliny, Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE)—who was Aristotle’s student—supported Aristotle’s research on animals by ordering the public to collaborate. Orders were given to some thousands of people throughout the whole of Asia and Greece, all those who made their living by hunting, fowling, and fishing, and those who were in charge of warrens, herds, apiaries, fishponds and aviaries, to obey [Aristotle’s] instructions, so that he might not fail to be informed about any creature born anywhere.

Modern scholars aren’t certain Alexander actually gave this order. Nonetheless, Aristotle’s writings about animals often refer to information he received from others who worked directly with animals, such as hunters, beekeepers, fishermen and herdsmen.

Home

United States

USA — IT Aristotle, Aelian and the giant octopus: The earliest 'citizen science' goes back...