Growing among professional workers, but still stuck when it comes to organizing nearly everybody else

Last Friday’s Wall Street Journal ran a front-page story documenting that American companies are now hiring workers for tens of thousands of dollars less than they were offering for the same jobs last year. In today’s cooling job market, new hires in retail are making less than half of what they would have made had they been hired for the same job last year. This pattern now affects workers in most of the economy’s sectors, though it’s not always so pronounced. New hires in what this survey terms the “science” sector are making about 25 percent less than peers who were hired last year.

This is precisely what one would expect, I should note, when the rate of unionization in the private sector is a paltry 6 percent. That’s not because American workers don’t like unions. The Gallup Poll’s annual public opinion survey of unions, conducted over August and released last week, found that 70 percent of Americans approved of them—close to the highest level of popularity unions have enjoyed since the mid-20th century—with just 23 percent disapproving.

Despite the steadily higher rates of approval, which have been growing throughout the past decade, unions still struggle to win new members in nonprofessional jobs. When workers on assembly lines and behind sales counters try to form or join a union, the near-universal response of American employers is to fire them. This is blatantly illegal behavior, but there are not even remotely serious penalties for it. That explains why it’s only workers who can’t be readily replaced, and thus can’t simply be fired, who’ve been successfully joining unions in the past several years: university teaching assistants, hospital interns, museum docents, software writers for gaming, think tank researchers, et al. As I noted in a previous article, college and university student-workers have voted to unionize over the past few years at rates of nearly 90 percent.

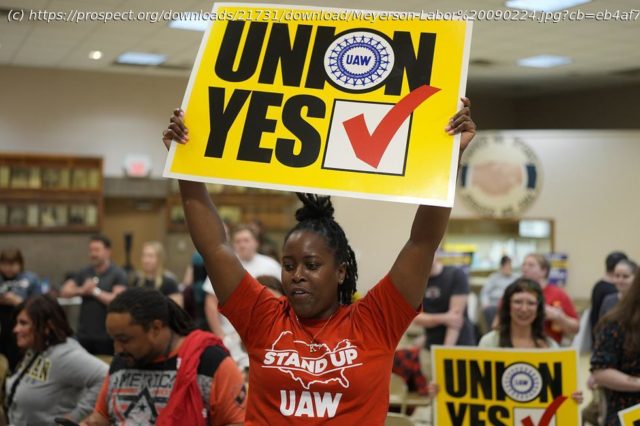

For workers who can easily be shown the door, however, voting in a union entails the steepest of uphill climbs. This year, however, we’ve seen two such groups of workers make it, provisionally, to the top. In April, the United Auto Workers won a decisive victory at Volkswagen’s plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. This was the UAW’s third such effort at the factory, by which time it had established a reputation as a skilled advocate for workers’ interests. It hadn’t sunk comparable roots among the workers at a Mercedes plant in Vance, Alabama, when it lost an election to represent the workers there one month later. Neither had it secured an agreement with Mercedes not to oppose their organizing campaign.