Johann Rehbogen is being tried for assisting in hundreds of murders while serving as a guard at the Stutthof concentration camp. He started work there when a teenager.

BERLIN — A 94-year-old man who served as a guard in Hitler’s SS clutched his cane as a bailiff wheeled him into a courtroom on Tuesday for the start of his trial on charges of assisting in the murder of hundreds of the 60,000 people who perished at the Stutthof concentration camp.

Johann Rehbogen was still a teenager when he began work as a guard at the camp, where he was stationed between June 1942 and September 1944. Because he was under the age of 21 at the time the alleged crimes were committed, the case is being tried before a juvenile court, where the maximum sentence he could face is 10 years in prison.

The indictment lists the deaths of more than 100 Polish prisoners and at least 77 Soviet P. O. W.s, as well as “an unknown number — at least several hundred — Jewish prisoners” killed in the gas chambers or by other means during his tenure at Stutthof, located on the Baltic Sea coast near what is now the city of Gdansk in Poland.

More than 140 mostly Jewish women and children were killed by injection of gas or phenol “straight to the heart of the individual prisoner,” while “an unknown number of prisoners died by various methods, including freezing in winter 1943-44,” according to the indictment.

“The defendant knew of the various methods of killing, he worked to make them all made possible,” said Andreas Brendel, a prosecutor for Nazi crimes in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, who read the charges to the court in Münster.

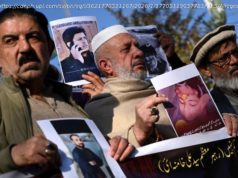

Seventeen survivors and their families, many of whom live in the United States, Israel and Canada, have joined the trial as co-plaintiffs.

Judy Meisel was 12 when she arrived at Stutthof. At 89, she can still remember standing naked, beside her mother, in line for the gas chamber. At the last minute, a guard indicated she could go back to the barracks. “Run, Judy, run!” her mother called to her in Yiddish. Ms. Meisel did and never saw her mother again.

“Stutthof was organized mass murder by the SS, made possible through the help of the guards,” she said in a written statement read to the court through her lawyer.

“He must take responsibility for what he did in Stutthof, take responsibility for participating in these unimaginable crimes against humanity,” she said. “For helping to murder my beloved mother who I missed for the rest of my life.”

No pleas are entered in Germany, but Mr. Rehbogen said through his lawyers that he would address the court at some point in the course of the trial, which is scheduled to last into January. Because of his age, trial sessions are limited to a maximum of two hours a day for no more than two nonconsecutive days a week.

For decades, the German justice system insisted that evidence of direct involvement in a Nazi-era crime was needed to charge a perpetrator, allowing countless low-ranking Nazis to live out their lives in peace.

That changed after 2011, when a Munich court found John Demjanjuk guilty of accessory to murder for having served as a guard at the Sobibor death camp. The court found there was no way he could have been oblivious to the killing taking place around him.

Mr. Demjanjuk, who disputed the accusation, died before his challenge to the ruling could be heard. But in 2015, the country’s highest criminal court upheld the conviction of Oskar Gröning, a former Auschwitz guard who was found guilty on the same argument of association, solidifying the legal precedent.

Mr. Brendel said investigators from his office studied hundreds of testimonies, as well as documents from other Nazi trials. They also flew to interview survivors, like Ms. Meisel, a resident of Minneapolis.

“Given the structure of the camp, we believe that the guards knew what was happening,” Mr. Brendel said. “The killings, especially the gassing and burning of corpses, could not be covered up.”

Established in 1941 as a labor camp, Stutthof later became a concentration camp. In 1944, a gas chamber was set up.

Ms. Meisel’s grandson, Benjamin Cohen, 34, attended Tuesday’s trial as part of a documentary he is making about her life.

“To have her statement read in court today and have her story heard by everyone in that courtroom was so monumental for her and for our family,” Mr. Cohen said. “It puts into perspective how important it is to acknowledge these crimes and never stop telling these stories.”