Willingness to risk his life for civil rights was essential to the quest for justice.

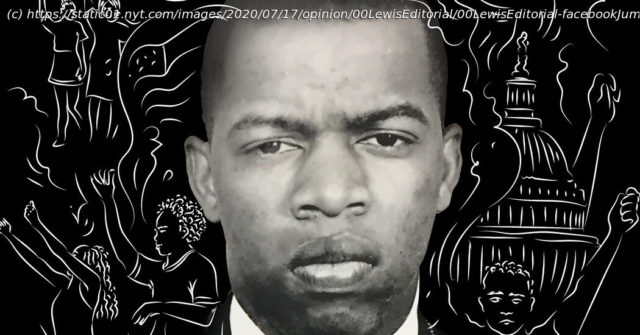

Representative John Lewis, who died Friday at age 80, will be remembered as a principal hero of the blood-drenched era not so long ago when Black people in the South were being shot, blown up or driven from their homes for seeking basic human rights. The moral authority Mr. Lewis exercised in the House of Representatives — while representing Georgia’s Fifth Congressional District for more than 30 years — found its headwaters in the aggressive yet self-sacrificial style of protests that he and his compatriots in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee deployed in the early 1960s as part of the campaign that overthrew Southern apartheid.

These young demonstrators chose to underscore the barbaric nature of racism by placing themselves at risk of being shot, gassed or clubbed to death during protests that challenged the Southern practice of shutting Black people out of the polls and “white only” restaurants, and confining them to “colored only” seating on public conveyances. When arrested, S. N. C. members sometimes refused bail, dramatizing injustice and withholding financial support from a racist criminal justice system.

This young cohort conspicuously ignored members of the civil rights establishment who urged them to patiently pursue remedies through the courts. Among the out-of-touch elder statesmen was the distinguished civil rights attorney Thurgood Marshall, who was on the verge of becoming the nation’s first Black Supreme Court justice when he argued that young activists were wrong to continue the dangerous Freedom Rides of early 1961, in which interracial groups rode buses into the Deep South to test a Supreme Court ruling that had outlawed segregation in interstate transport.

Mr. Marshall condemned the Freedom Rides as a wasted effort that would only get people killed. But in the mind of Mr. Lewis, the depredations that Black Americans were experiencing at the time were too pressing a matter to be left to a slow judicial process and a handful of attorneys in a closed courtroom. By attacking Jim Crow publicly in the heart of the Deep South, the young activists in particular were animating a broad mass movement in a bid to awaken Americans generally to the inhumanity of Southern apartheid. Mr. Lewis came away from the encounter with Mr. Marshall understanding that the mass revolt brewing in the South was as much a battle against the complacency of the civil rights establishment as against racism itself.

On “Redemptive Suffering”

By his early 20s, Mr. Lewis had embraced a form of nonviolent protest grounded in the principle of “redemptive suffering”— a term he learned from the Rev. James Lawson, who had studied the style of nonviolent resistance that the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi had put into play during British colonial rule. The principle reminded Mr. Lewis of his religious upbringing and of a prayer his mother had often recited.

In his memoir “Walking With the Wind,” written with Michael D’Orso, Mr. Lewis explains that there was “something in the very essence of anguish that is liberating, cleansing, redemptive,” adding that suffering “touches and changes those around us as well.