When Los Angeles shuttered its last streetcar in 1963, the Bay Area was already planting the seeds of BART, the expansive rail system that embodies a common refrain in the longstanding competition …

When Los Angeles shuttered its last streetcar in 1963, the Bay Area was already planting the seeds of BART, the expansive rail system that embodies a common refrain in the longstanding competition between Southern and Northern California: Angelenos are gas-guzzlers stuck in parking-lot traffic, while the Bay Area has built an enviable transit network.

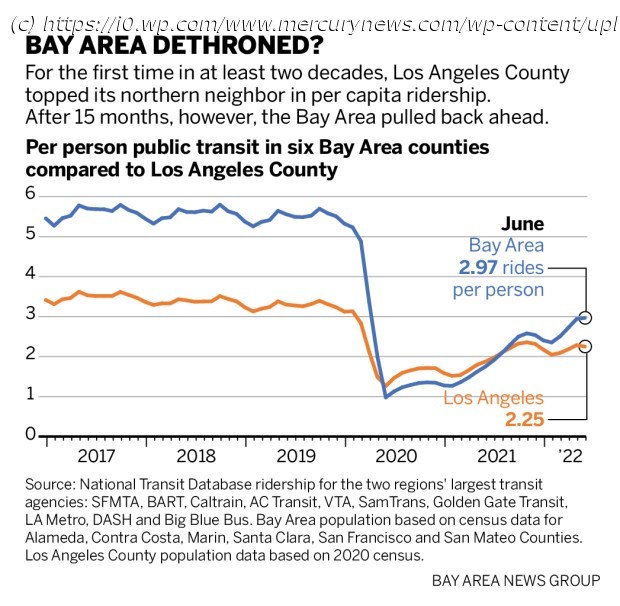

But over the past two and a half years, the Bay Area’s claim to California’s mass transit throne has been deeply eroded, if not undone. L.A. now has more people riding buses, light rails and trains than the Bay Area. And even when accounting for the Bay Area’s far smaller population, L.A.’s per-capita transit ridership temporarily surpassed its Northern California neighbor for the first time in at least two decades.

How big was the turnaround? In 2019, transit riders in six Bay Area counties took 43 million more trips than L.A. County, which is over a third larger by population. But in 2021, Los Angeles racked up over 83 million more transit trips than the Bay Area – a staggering threefold reversal, according to a Bay Area News Group analysis of federal data for the two regions’ largest transit agencies.

It’s a titanic shift starting in the depths of the pandemic that could remake California’s transit landscape. With the Bay Area’s once thriving commuter-heavy trains suffering some of the country’s biggest passenger losses and Los Angeles’ bus riders propelling a surprising ridership recovery in Southern California, the state’s two biggest metro regions are now living test cases for mass transit’s role in a post-pandemic future.

At the heart of the upheaval is a question that will define the state’s transit planning for years to come: Should we continue building pricey rail projects that cater to white-collar commuters who fled public transit or should we invest in the bus riders who never left?

The implications are major, calling into question public transit’s role in the climate change battle and resurfacing long-standing tensions between planning transit for more privileged rail riders over lower-income bus riders.

“What happened in the pandemic is the whole script flipped,” said Brian Taylor, a transportation expert at UCLA.

The driving force behind the Bay Area and L.A.’s current ridership fortunes is not a flourishing mass transit system in Los Angeles. Angelenos did not suddenly ditch their cars for the metro. Instead, it’s a story of two hobbled transit systems clawing back their pre-pandemic riders at vastly different rates. As of June 2022, Los Angeles County has recovered 71% of its ridership compared to 55% in the Bay Area.

Bay Area office workers like Stephen Lanham are behind one of the nation’s worst ridership recoveries as techies, lawyers and financial analysts left transit for the safety of their cars and to work from home.

After years of being a daily BART user, Lanham, an engineer, said goodbye to hopping on trains with strangers when pandemic lockdowns kicked in. “I went two years without riding BART,” said Lanham, who has returned in recent months to riding rail twice a week. Besides his office shifting to remote work, Lanham did not want to risk spreading a COVID-19 infection to his newborn child.

His changing routine is typical. Across the Bay Area’s seven largest rail and bus agencies – including Muni, BART, Caltrain, AC Transit and VTA – riders took 283 million fewer transit rides in 2021 versus 2019. That is 80% higher than 157 million rides lost among Los Angeles County’s main transit operators.

Taylor of UCLA said the wide disparity is because Bay Area transit ridership was so heavily skewed toward commuters heading into buzzing San Francisco office buildings. “The share of trips on BART that began or ended at the four downtown San Francisco stations was going up every year. Right up to the pandemic,” said Taylor. “And then that cut off.”

The collapse in transit focused around downtown San Francisco is so dramatic that Los Angeles’ web of subways and light rails, which is smaller and notoriously lacks an LAX airport connection, is now regularly moving more people than BART for the first time since the Federal Transit Administration started collecting monthly ridership data 20 years ago.

Домой

United States

USA — IT The Bay Area was California’s transit mecca. Now car-crazy L.A. has more...