If the composition and dissemination of verse is as volatile as anything in the cosmos, the reading of it can also be as various and puzzling.

Knowing someone on the field as a fellow cricketer is one thing. So too becoming privy to his engaging forays into Maharashtrian antiquities. Quite something else it is to listen to Professor Girish Kulkarni of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research giving a public lecture on the properties of the Universe in its first billion years.

Among Girish Kulkarni’s beguiling analogies and metaphors, I am particularly struck by his comparison of the way the further you venture out into space, that is also, given the speed of light, back in time, what is known becomes more fragmentary in the way archaeologists digging down under a modern city usually find fewer remains as they go until there is nothing at all.

To this model or metaphor, apparently, there is one exception. At a certain distant “epoch” in space, beyond the imagining except in esoteric mathematical formulae, there is a “zone” so clear it is as if an archaeologist, digging down into ever lower levels, has come upon a city – some lost Harappa or Pompeii – relatively well preserved. This is a surprise and creates a puzzle for cosmologists since it fits ill with the otherwise established pattern of a diminishing series.

As a woolly-minded versifier, I find myself provoked to toy with the possibility of an analogy between this riddle of contemporary cosmology and the surprises that can be thrown up by the composition of verse as well as its history.

First, a historical example. Let me ask a question such as Girish Kulkarni might ask about versification. Which is the most widely known verse of English poetry? Perhaps something by Shakespeare? Or Wordsworth? Or Byron?

Well, that might be so but my own random sample taken from many rambles across the world might suggest by way of answer a verse with which you will surely be familiar. By chance, it is curiously appropriate for cosmology:

I have found so many people, especially but not exclusively children, from Beijing to Budapest, from Madrid to Montreal, who, even when knowing little English, can recite this verse. I have seen copies of it inscribed on plates and on wall-hangings.

Of course you know this verse, surely we all do, but, since we tend to remember poetry just in fragments, do you remember – I didn’t – how it goes on and elaborates on the theme of the twinkling star?

The movement of the verse is tied to a constant refrain of its iconic first line in a way that is common to Indian prosody. It returns to it finally via a line no doubt equally congenial to cosmologists as they confront newer objects of astronomical ignorance such as black holes and dark matter: “Though I know not what you are, twinkle, twinkle, little star”.

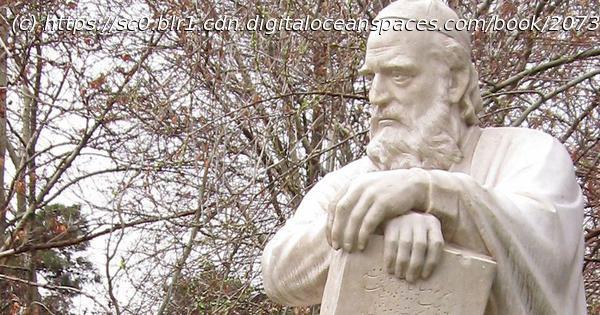

As with much poetry, often assigned for reasons good as well as bad to Anon, you may have forgotten or never known the name of the author of “The Star”? It is Jane Taylor who, along with her sister Ann, was a phenomenally successful and well-loved writer in the Victorian era and beyond, at home and abroad.

If you have seen the film PK, you may also be surprised to learn that it is indirectly, as stories by Browning and Mark Twain were directly, indebted to another of Jane’s works, “How It Strikes a Stranger”. This moral tale pioneered a genre whereby a stranger from outer space – Jane’s from her twinkling Evening Star – arrives on Earth and exposes while experiencing the absurdities of human behaviour. Jane’s particular target was Man’s greed for wealth and possessions in the face of mortality.