India must learn the art of building legal, regulatory and social frameworks that make creative destruction an engine of inclusive growth with social cohesion.

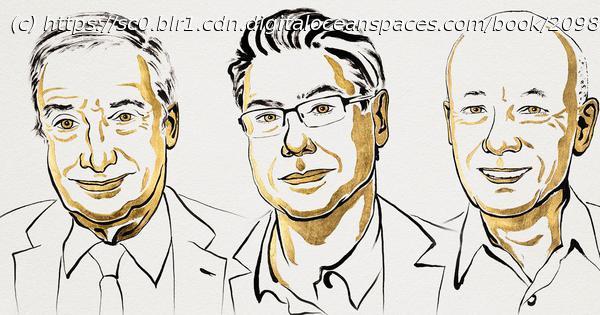

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics feels less like an intellectual honour and more like the next chapter in a continuing conversation about how economies grow. The combined message of Joel Mokyr (Northwestern University, US), Philippe Aghion (The London School of Economics and Political Science, UK) and Peter Howitt (Brown University, USA) is plain and urgent: growth is an evolutionary, institutional process – one that depends on knowledge, the incentives to create it and the legal and regulatory scaffolding that turns ideas into widespread prosperity.

Put simply, Mokyr asks: how does useful knowledge accumulate? Aghion and Howitt ask: how does that knowledge translate into growth through innovation – the Schumpeterian “gale of creative destruction”? For India, a country large in scale and rich in human capital but uneven in institutions and outcomes, the answers matter a great deal.

Conventional policy debates often begin with inputs: more factories, more roads, more graduates. There’s truth to that. But Mokyr reminds us that inputs are necessary, not sufficient. Economic growth is not just a mechanical function of capital and labour: it is the product of a social architecture that allows ideas to be generated, tested, shared and scaled. Property rights, enforceable contracts and rule of law are necessary conditions – but Mokyr goes further. He highlights the informal norms, communication networks and institutional experiments that let useful knowledge accumulate.

For India, this is a practical admonition. The country has dramatically expanded its higher education footprint and produced a huge number of graduates. Yet scale without research culture, translational linkages and intellectual pluralism produces only incremental gains. Mokyr’s lesson: build institutions that nurture reproducible research, encourage industry–university collaboration, and protect the space for experimentation and dissent. Funding labs matters. So does the policy that connects those labs and make them relevant.

Aghion and Howitt give us the mechanics. They formalise Joseph Schumpeter’s insight that growth comes from cycles of innovation that displace established technologies and firms. Crucially, their models show why temporary monopoly rents can be socially desirable: they create the expected payoff necessary to justify risky, long-term research and development.

Домой

United States

USA — mix Knowledge and creative destruction: Lessons for India from the 2025 Nobel economics...