January 4, 2017

January 4, 2017

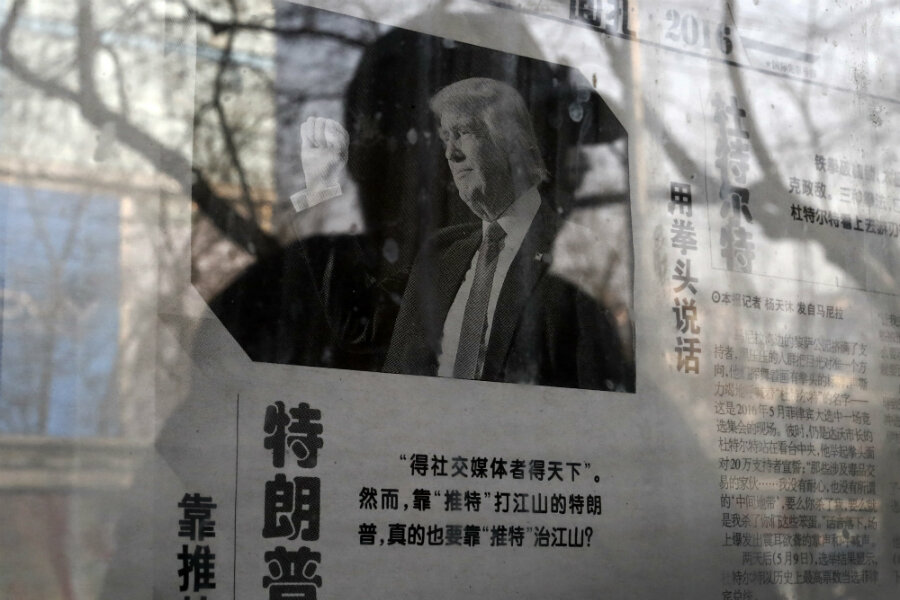

— On Sunday, after North Korea said it was close to testing a nuclear-equipped missile that could reach the United States, president-elect Donald Trump wrote on Twitter, “It won’t happen!”

Maybe it was breezy skepticism, or maybe it was a red line. For many US officials and North Korea experts, the right path for a Trump administration to take in dealing with the country’s rulers seems nearly as murky, even as some say that it could develop the capacity to hit the US mainland over the next four years.

That potential puts the US in a tough spot, highlighting both the risks of pre-emptive action and previous administrations’ unsuccessful maneuvers to push North Korea away from nuclear proliferation.

Since the presidency of Bill Clinton, the US has tried to exchange aid for disarmament. A 1994 deal that would have allowed North Korea to produce nuclear energy and normalized ties with the US failed after it was discovered that Pyongyang had sought to use uranium for weapons. The North also withdrew in 2009 from China’s attempt to broker nuclear negotiations with four other countries, and a 2012 Obama administration food-aid deal that would have frozen North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs was abandoned just weeks into the effort, after the North tried to launch a long-range rocket.

Mr. Trump said on the presidential campaign trail that he was willing to meet with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un. He hasn’t outlined any further steps, though a transition team adviser told Reuters that “a period of serious sanctions” would be “a major part of any discussion on the options available here.”

That’s been the main strategy since the North conducted the first of its five nuclear tests, in 2006, though the country’s economic and diplomatic isolation tends to limit the effectiveness of such sanctions. And Trump’s antagonistic view of China might further hinder long unsuccessful US attempts to get North Korea’s closest ally to cut back on trading with its neighbor, for whom it supplies a significant economic lifeline.

US officials who did not want to be identified told Reuters that if the North were to carry out a long-range missile test, the US military would have three options: allow it to proceed, intercept the missile after its launch, or strike before the launch to pre-empt it.

Jeffrey Lewis, an arms control expert at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, in Calif., told Reuters that US missile defenses wouldn’t have an easy time shooting down a test missile. And he underscored the risks of military action, which could provoke retaliation against regional allies.

North Korean nuclear and missile test sites, and the factories that supply them, are scattered across the country, he said.

“There’s a warren of tunnels under the nuclear site. And an ICBM can be launched from anywhere in the country because it’s mobile. You might as well invade the country,” Dr. Lewis said.

This report contains material from the Associated Press and Reuters.