Over the course of that half-century, Jethro Tull has proved to be a true musical chameleon — with forays into folk, blues, classical and hard rock.

Ian Anderson recalls his first visit to Chicago in 1969 as one of great anticipation and anxiety. His budding new band Jethro Tull was playing at the Kinetic Playground as support for Led Zeppelin.

“You were aware there was pretty hearty competition to get noticed when you were playing alongside Zep,” says Anderson. “We as a lowly opening act had to give a good account of ourselves and try to not be steamrolled by what became, in short order, one of the world’s greatest rock bands ever. More so because they didn’t just do rock. They went into elements of folk music and world music.”

Anderson was also eager to visit Chicago because of its contributions to blues music. Ever since he was a teenager growing up in England, he idolized African-American bluesmen such as Muddy Waters for their acoustic country-fused blues.

“What resonated with me most was the simplicity, the purity, the fact that it was very exotic,” he says. “It wasn’t the commercialized and rather thin-sounding music of British pop music, which was cheesy and upbeat and friendly and full of sentiments that were not really about the real world.”

While he typically shies away from nostalgia, he has a special reason now to reminisce about his career — his current tour is celebrating the 50th anniversary of Jethro Tull, whose hits include “Bungle in the Jungle,” “Broadsword,” “Living in the Past,” “Aqualung” and “Locomotive Breath.” Over the course of that half-century, Jethro Tull has proved to be a true musical chameleon, with forays into folk, blues, classical and hard rock. They are pioneers of the progressive rock sound and were one of the first bands to incorporate flute in rock music.

Since forming in 1968, Jethro Tull has released 30 albums and sold more than 60 million copies worldwide. The anniversary concerts take audiences on a trip from the band’s earliest formative material to its biggest hits. It also introduces audiences to many of the thirty-six studio and/or touring members that have been part of Jethro Tull’s history. Anderson is thankful for each incarnation of the band.

“Thirty-six different members of Jethro Tull have been able to claim their part in that history,” Anderson says. “I like to fondly remember all their contributions and interactions both socially and musically.”

Working with so many different musicians inspired Anderson to write challenging and thoughtful songs, dabbling in various genres. There were not many dull moments creatively as each member came in with his own unique musical skills and background.

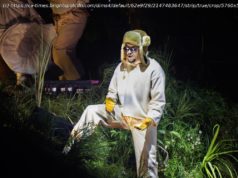

Ian Anderson’s flute-playing made Jethro Tull one of the first rock bands to incorporate the instrument into its body of work.| Travas Latam Photography

“It’s energizing because you don’t feel limitations,” says Anderson. “If you work in a certain genre of music, it may be productive [in that] you concentrate all your efforts on doing one kind of thing. But for me it would be rather limiting because I’m naturally curious about music and naturally inclined to explore options. Sometimes those options are stylistically different from the last thing I did.”

Anderson’s current band features David Goodier (bass), John O’Hara (keyboards), Florian Opahle (guitar) and Scott Hammond (drums). He’s enjoying this lineup as they do justice to the many versions of Tull.

“They have to be capable technically in terms of the nuances and understanding of the music,” he says. “They’re not playing just one edition of Jethro Tull from the early ’70s. So, these guys have to be versatile but not just paying lip service to it. They have to be steeped in many musical styles and a historical understanding of the development of pop and rock music over the last 50 years.

“Hopefully that’s something they’re able to do and bring their own little touch to the outcome so they’re not just replicating what someone else played. In some discreet way interpreting it. It’s about finding the balance between replicating and interpreting,” Anderson says.

When he’s performing, Anderson says he doesn’t think of a song as being a certain number of years old. Instead it’s about when he last performed the song live.

“It’s really hard to be nostalgic about music that you played not 49 years ago but 24 hours ago,” Anderson says.

Improvisation plays a big part in keeping arrangements vibrant. “It’s a little different every night, little nuances and slightly different content.”

He’s proud many songs are still socially relevant today. For example, “Aqualung” is about homeless and “Locomotive Breath” is about issues relating to population growth.

“Topics of religion and other social aspects — those are things that always interested me as a songwriter and perhaps what keeps it fresh for me, that I don’t feel like I’m sucked into nostalgia when I walk onto a stage,” Anderson says. “If you tune into CNN or Fox News, you’re going to be confronting issues which very well may be reflected by me in songs over the years. So, some things don’t really change.”