In the realm of medicine, what you don’t know can indeed kill you. When it comes to the novel coronavirus, technically known as SARS-CoV-2,…

In the realm of medicine, what you don’t know can indeed kill you.

When it comes to the novel coronavirus, technically known as SARS-CoV-2, and the disease it causes, called COVID-19, what experts are still trying to understand sometimes seems to outweigh what they can say for certain.

That is little surprise to any infectious-disease researcher: Highly contagious diseases can move through communities much more quickly than the methodical pace of science can produce vital answers.

What we do know is that the coronavirus apparently emerged in China as early as mid-November and has now reached more than 185 countries, infected more than 3.9 million people, and killed at least 272,000. Population-level studies using new testing could boost case numbers about 10-fold in the US.

As hospitals around the world strain to care for patients with blood clots, strokes, and long-lasting pneumonia and respiratory failure, scientists are racing to study the coronavirus, spread life-saving information, and combat dangerous misunderstandings.

Here are 11 of the biggest questions surrounding the coronavirus and COVID-19, and why answering each one is critically important.

The first coronavirus infections was thought to have emerged in a wet market in Wuhan, in China’s Hubei province. But newer research suggests the market may simply have been a major spreading site.

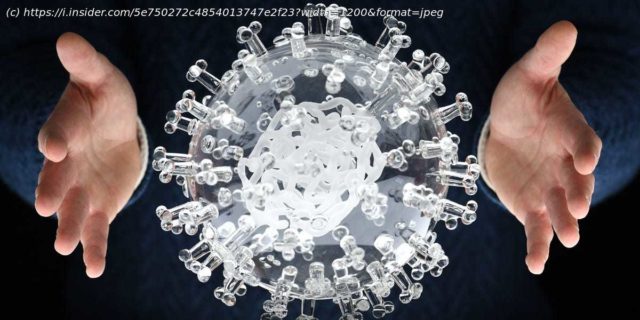

Researchers are fairly certain that the virus — a spiky ball roughly the size of a smoke particle — developed in bats. Lab tests show that it shares roughly 80% of its 30,000-letter genome with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), a virus that also came from bats and triggered an epidemic in 2002 and 2003. It also shares about 96% of its genome with other coronaviruses in bats.

Mounting evidence continues to undercut the conspiracy theory that the virus came from a Chinese laboratory, however.

Still, researchers still aren’t sure how the coronavirus made the jump from bats to humans. In the case of SARS, the weasel-like civet became an intermediate animal host. Researchers suspect that civets, pigs, snakes, or possibly pangolins — scaly nocturnal mammals often poached for the keratin in their scales — were a likely intermediary host for the new coronavirus.

A research group in China published early, non-peer-previewed results that pointed to pangolins (which can die from coronaviruses) as the vector for humans, finding 99% genetic similarity. But it could also be that the virus jumped straight from bats to humans.

Why it matters: Understanding how novel zoonotic diseases evolve and spread could lead to improved tracing of and treatments for new emerging diseases.

Global tallies of cases, deaths, recoveries, and active infections reflect only the confirmed numbers — researchers suspect the actual number of cases is far, far larger.

For every person who tests positive for the novel coronavirus, there may be about 10 undetected cases. This is because testing capacity lags behind the pace of the disease, and many governments — including in the US — failed to implement widespread testing early on.

Contrary to the claims of Elon Musk and others, deaths from COVID-19 are also likely being significantly undercounted.

Why it matters: An accurate assessment is critical in helping researchers better understand the coronavirus‘ spread, COVID-19’s mortality rate, the prevalence of asymptomatic carriers, and other factors. It would also give scientists a more accurate picture of the effects of social distancing, lockdowns, contact tracing, and quarantining.

Setting aside any debate about whether they’re alive (or something else), viruses are small and streamlined particles that have evolved to make many, many copies of themselves by hijacking living cells of a host.

The measurement of a virus‘ ability to spread from one person to another is called R0, or R-naught. The higher the value, the greater the contagiousness — though it varies by region and setting. The novel coronavirus‘ average R0 is roughly 2.2, meaning one infected person, on average, spreads it to 2.2 people. But it had a whopping R0 of 5.7 in some densely populated regions early in the pandemic.

The seasonal flu, by contrast, has an R0 of about 1.3.

Researchers don’t yet understand why the coronavirus is so effective at spreading, though they have some ideas. One is that its surface proteins, which enable the virus to stick to host cells and invade them, attach with an especially strong latch, The Atlantic’s Ed Yong reported.

The new coronavirus also seems to infect the upper and lower respiratory tracts, unlike SARS, which infected primarily tissue deeper in the lungs. And coughing — a signature symptom of COVID-19 — helps spread viruses in tiny droplets, especially in confined places. There’s also some evidence the virus infects intestinal cells and may be spread by feces.

Additionally, it’s thought that 25% to 50% of people infected show few to no symptoms, helping facilitate the virus‘ spread.

Why it matters: Knowing how a virus gets around can help everyone better prevent its spread.

Start

United States

USA — mix 11 critical, unanswered questions about the coronavirus and COVID-19, the diseases it...