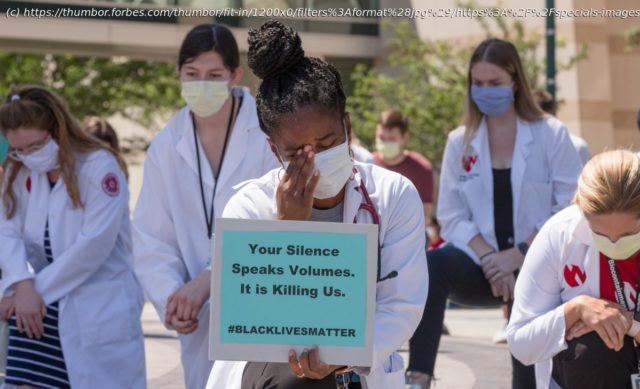

In their own words, this piece features a range of voices, from pathologists to psychiatrists, who will tell you what it means and feels like to be a Black doctor right now in the middle of two pandemics, COVID-19 and the national reckoning with racism.

The experience of frontline healthcare workers during the coronavirus pandemic has been and remains headline news. We know what the experience is like without personal protective equipment, to be infected with COVID-19, and the potential risk for serious mental health outcomes. What we don’t know is how this is disproportionately affecting Black doctors. Black doctors who have seen more patients who look like them be infected and die from coronavirus. Black doctors who go to work and can feel isolated and alone in their lived experiences, as they make up only 5% of the physician workforce. And, Black doctors who once again witnessed the brutal murder of a Black man, George Floyd, on camera by a police officer.

We can hypothesize based on what we know and say this will affect their mental health more, but we also need to hear directly from them. This is the time to listen and learn and center their experiences. In the first half of this two-part series, in their own words you will hear from a range of voices, from pathologists to psychiatrists, who will tell you what it means and feels like to be a Black doctor right now in the middle of two pandemics, COVID-19 and the national reckoning with racism.

When the news about George Floyd broke, I went through a myriad of emotions. The one that has been the most consistent is the pain. It’s a raw, visceral pain. Every time this happens (and it is heartbreaking to have to keep saying every time), I think „That could have been my brother, father, brother-in-law, cousins, etc“. I think back to when I’ve gotten pulled over; „Keep your hands on the wheel, be respectful, and maybe this will be OK.“ I am so tired.

I have gotten used to being an only. As a black woman in pathology, there is a sprinkling of us about the country. In many subspecialties of pathology, such as bone and soft tissue, genitourinary, medical renal, and forensics, we are very few. So, imagine this scenario: a poorly written press release interpreting the preliminary findings of the autopsy lacking the word everyone was waiting to see: homicide. Instead of seeing that word, the release seemed to accuse George Floyd. Suddenly, I was being asked to interpret this „autopsy report“. Gaslighting at its finest. I found myself in an intersection between my race and my profession.

By defending the presence of forensic pathology, and in particular, this forensic pathologist, was I siding against my people? I was afraid many would think so. The morning after the press statement was released, I took to Twitter. @DrFNA was on a mission. I took great care in my tweets. I made it clear that I was hurting. I explained the difference between coroners and medical examiners. I also explained, with much rightful outrage regarding the press release, that this was not the preliminary autopsy report, and that, despite our rage, we needed to wait. As a community, we are so used to corruption in the handling of cases involving us. It became a “here we go again” moment. This pain was compounded because there was a video that showed it all.

I have been trolled on Twitter, so I am no stranger to insults. Much to my surprise, there was no negativity directed at me. What I thought would come to pass did. The next morning, the Hennepin County Medical examiner’s office released the preliminary report. Manner of death: homicide. The word we were looking for. What we saw on the video, 8 minutes and 46 seconds of a knee in the back of George Floyd, screaming for his mother. Screaming that he couldn’t breathe. For a fleeting moment in time, what we saw was justified.

It’s no longer enough to not be racist. We all must rise against it. Many are now talking the talk but must now walk the walk. It hurts that the black body count continues to rise because people see us as less than human. See us as the beautiful people we are. Please. I was born black, and I will die black. I just don’t want to die tired.

I’m tired. I’m frustrated. I’m overwhelmed. I am stretched thin. I don’t feel like I have enough time in the day. I’m not ready to have a conversation with you, but it seems like I have to. These are all thoughts, phrases, and utterances that I have expressed to my colleagues over the past the few weeks. Just as we were stabilizing from the COVID-19 pandemic and recognizing that we had likely made it through the first wave, we were hit again, but this time with police brutality. These past few weeks have been an outright assault on my mental health. Sleep is a luxury, sadness is commonplace, and anger comes quickly when off-putting comments are uttered by colleagues, even those considered friends.

When I am in the Emergency Department caring for patients, I am a physician. It is my career, it is my profession. It is not who I am though. It is not what defines me. If it were up to me, I would describe myself as a Christian, husband, father, Texan, lover of many things including beaches, BBQ, mojitos, and a good chocolate chip cookie recipe. Unfortunately, that is not how this society in America would describe me. Reflexively, without knowing anything about me, this society defines me as Black man and along with that ascribes the stereotypes to me. When people know who I am and what I do, it is easy to know these attributes about me. When the assumptions are made without knowing me the default options are often that “I am less than” or a threat.

Being a Black physician in times of injustice means checking your emotions at the door because your professionalism may be called into question if you bring in concerns from the outside world into the practice of medicine. It often feels as if you have to strip your other identities away and carry yourself in a manner that is stoic and aloof to society while being compassionate to the patient in front of you. As George Floyd struggled and pleaded “I can’t breathe.” I couldn’t breathe because I felt that pain. As a doctor it would be malpractice and a violation of the code of ethics of the profession to ignore someone the way the police officer did George Floyd. Sadly enough shortly after we saw the video, a case was presented at our department’s Morbidity and Mortality conference and the chief complaint was “I can’t breathe.” I immediately drew parallels to the two situations. So did the other Black physicians in the group; disappointingly, many of my White colleagues did not see the same parallels. I sent an email to the group to explain to them what I was feeling and likely what the other Black physicians in our group were feeling. Unfortunately, it feels as if it may have fallen on deaf ears as many struggled to reply, while others seemed to have shied away despite me openly expressing discontent. It took a week for my hospital, medical school, and the professional organizations that I belong to ultimately speak up and denounce racism, call for societal reform, and speak out against police brutality. It seems as if no one wanted to be the first to speak up. It also seems as if everyone was scared to say the wrong thing, not realizing that saying nothing was just as bad if not worse.

With the social unrest on full display as protests rose across the country, I was driving into work for an overnight shift. Because of my clinical responsibilities I was not able to join in the peaceful protest. My duality as a physician and a Black man were in conflict.

James Baldwin once said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in rage almost all the time.” To be a physician and to be a Black man is to be in a constant state of rage but to have to bottle those emotions up even if it may be to your own detriment.

#GeorgeFloyd, #Minnesota, and #BlackLivesMatter trended on Twitter. Just reading those three lines, I knew two things: another unarmed Black man was murdered by police violence and my heart couldn’t take reading it.

A few days before the news broke, I suddenly developed a pounding heart rate. Probably anxiety, I thought. When the pounding followed me the next couple of days, I tried every calming trick that I know: breathing exercises, prayer, meditation, etc.