Immortalised as a three-year-old survivor, Spencer Bailey has a unique insight on how the dead should be remembered.

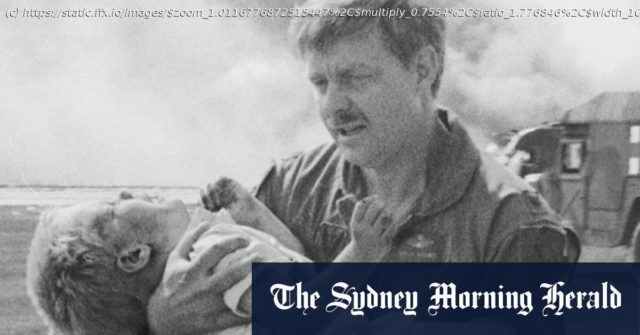

Spencer Bailey is carried after the 1989 crash-landing of United Flight 232 in Sioux City, Iowa. Credit:Gary Anderson / Sioux City Journal / Zumapress.com In 1989, Spencer Bailey survived a plane crash in Sioux City, Iowa, that killed 112 people, including his mother. He was three-and-a-half. A photograph recording his rescue was transformed into a memorial sculpture, The Spirit of Siouxland. Still haunted by his mother’s death, the 35-year-old remains conflicted by the sculpture. “Memorials don’t typically represent the living, and people assumed I died,” he says via Skype from New York. As Bailey wryly observes, he stands in the company of dictators as one of the few people to have a monument created in their honour while they are still living. “I’m sure there were good intentions involved in building the memorial,” he says. “But I don’t think that it was the most effective form of memorial-making. It’s not that I’m uncomfortable with my image being used. It was more that I prefer to argue for abstract memorials. Because they allow multiple interpretations and the visitor to respond in their own way.” The Spirit of Siouxland Flight 232 Memorial by Dale Lamphere. Credit:Spencer Bailey Experiencing this “cast in bronze reality of my life”, the former editor-in-chief of design magazine Surface felt ideally placed to write about memorials. In Memory Of examines 63 abstract memorials from around the world, created over the past 40 years. They range from recent history, such as the 9-11 World Trade Center memorial (Reflecting Absence by Michael Arad and Peter Walker), to belated reckonings on slavery, and even Norwegian witch burnings (a collaboration between Pritzker prize-winning architect Peter Zumthor and artist Louise Bourgeois). If Bailey’s own sculpture sparked his interest, Maya Lin’s 1982 Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC is the book’s ground zero. “If this book were to have a family tree, most of its branches would stem from Lin’s memorial,” Bailey writes. Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial. Credit:Getty Images Lin’s simple V-shaped slash in the landscape, lined in black polished granite and etched with the names of some 58,000 US dead, was both the culmination and starting point of a sophisticated formal language in memorial design, Bailey says. The sheer variety and scale of memorials in the book illustrate the ability of abstract forms to be both compelling and complex. They range from the blunt force of 816 Corten Steel hanging ‘‘coffins’’ in the ‘‘lynching memorial’’ (the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama by MASS Design Group), to Micha Ullman’s modest underground Empty Library in Berlin, a memorial to Nazi-era book burning, where viewers look down onto empty shelves. National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery, Alabama. MASS Design Group (2018). Credit: Alan Ricks / MASS Design Group “It’s not about bigger is better,” says Bailey. “It’s about intent and message – and ultimately the quality of the execution. What these memorials do that’s so profound is encourage us to slow down and look inward,” he says. “Buildings don’t do that generally.” Melbourne architect Kerstin Thompson agrees. For the new Jewish Holocaust Centre in Elsternwick (opening in September 2021), she found abstraction offered the most powerful way for architecture to “speak of the unspeakable”. Not for her the “heavy-handed archi tropes that quote Auschwitz and Holocaust infrastructure”, such as barbed wire and gantries. The bunker is another trope she avoids: while it offers security, it’s not exactly welcoming. Instead, Thompson’s facade of brick and glass conjures abstract memories of Kristallnacht, when bricks were thrown through Jewish shopfronts. The glass bricks are practical: they’re transparent, welcoming and bomb-resistant.