The pivotal failure of the coronavirus crisis has never been addressed.

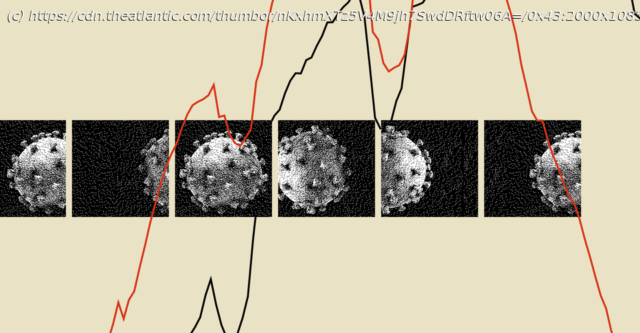

A few minutes before midnight on March 4,2020, the two of us emailed every U.S. state and the District of Columbia with a simple question: How many people have been tested in your state, total, for the coronavirus? By then, about 150 people had been diagnosed with COVID-19 in the United States, and 11 had died of the disease. Yet the CDC had stopped publicly reporting the number of Americans tested for the virus. Without that piece of data, the tally of cases was impossible to interpret—were only a handful of people sick? Or had only a handful of people been tested? To our shock, we learned that very few Americans had been tested. The consequences of this testing shortage, we realized, could be cataclysmic. A few days later, we founded the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic with Erin Kissane, an editor, and Jeff Hammerbacher, a data scientist. Every day last spring, the project’s volunteers collected coronavirus data for every U.S. state and territory. We assumed that the government had these data, and we hoped a small amount of reporting might prod it into publishing them. Not until early May, when the CDC published its own deeply inadequate data dashboard, did we realize the depth of its ignorance. And when the White House reproduced one of our charts, it confirmed our fears: The government was using our data. For months, the American government had no idea how many people were sick with COVID-19, how many were lying in hospitals, or how many had died. And the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic, started as a temporary volunteer effort, had become a de facto source of pandemic data for the United States. After spending a year building one of the only U.S. pandemic-data sources, we have come to see the government’s initial failure here as the fault on which the entire catastrophe pivots. The government has made progress since May; it is finally able to track pandemic data. Yet some underlying failures remain unfixed. The same calamity could happen again. Data might seem like an overly technical obsession, an oddly nerdy scapegoat on which to hang the deaths of half a million Americans. But data are how our leaders apprehend reality. In a sense, data are the federal government’s reality. As a gap opened between the data that leaders imagined should exist and the data that actually did exist, it swallowed the country’s pandemic planning and response. The COVID Tracking Project ultimately tallied more than 363 million tests,28 million cases, and 515,148 deaths nationwide. It ended its daily data collection last week and will close this spring. Over the past year, we have learned much that, we hope, might prevent a project like ours from ever being needed again. We have learned that America’s public-health establishment is obsessed with data but curiously distant from them. We have learned how this establishment can fail to understand, or act on, what data it does have. We have learned how the process of producing pandemic data shapes how the pandemic itself is understood. And we have learned that these problems are not likely to be fixed by a change of administration or by a reinvigorated bureaucracy. That is because, as with so much else, President Donald Trump’s incompetence slowed the pandemic response, but did not define it. We have learned that the country’s systems largely worked as designed. Only by adopting different ways of thinking about data can we prevent another disaster: 1. All data are created; data never simply exist. Before March 2020, the country had no shortage of pandemic-preparation plans. Many stressed the importance of data-driven decision making. Yet these plans largely assumed that detailed and reliable data would simply… exist. They were less concerned with how those data would actually be made. So last March, when the government stopped releasing testing numbers, Nancy Messonnier, the CDC’s respiratory-disease chief, inadvertently hinted that the agency was not prepared to collect and standardize state-level information. “With more and more testing done at states,” she said, the agency’s numbers would no longer “be representative of the testing being done nationally.” When we started compiling state-level data, we quickly discovered that testing was a mess. First, states could barely test anyone, because of issues with the CDC’s initial COVID-19 test kit and too-stringent rules about who could be tested. But even beyond those failures, confusion reigned. Data systems have to be aligned very precisely to produce detailed statistics. Yet in the U.S., many states create one sort of data for themselves and another, simpler feed to send to the federal government. Both numbers might be “correct” in some sense, but the lack of agreement within a state’s own numbers made interpreting national data extremely difficult. The early work of the COVID Tracking Project was to understand those inconsistencies and adjust for them, so that every state’s data could be gathered in one place. Consider the serpentine journey that every piece of COVID-19 data takes.