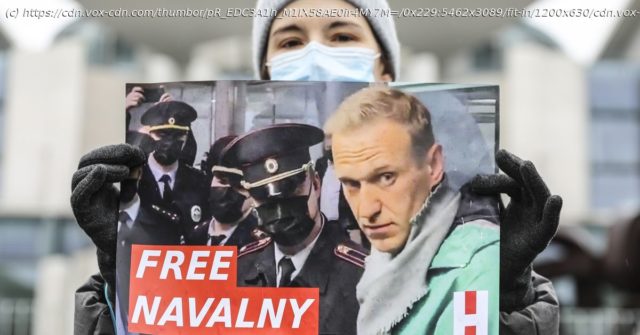

Alexei Navalny, the arrested Russian opposition leader, sparked protests against Vladimir Putin with a YouTube video. Now, his hunger strike in prison is pressuring Putin again.

The greatest challenger to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s rule is a man whose name the dictator won’t say and whom he has tried to kill: Alexei Navalny. Having defiantly returned to Russia after surviving a brazen assassination attempt only to be immediately detained and thrown in jail upon arrival, the opposition leader and anti-corruption crusader has rallied tens of thousands of supporters to his cause like never before — a real sign of trouble for Putin’s hold on power. Alexei Navalny has spent over a decade trying to overthrow Putin. Through slick videos, public mobilization, and even an ill-fated presidential run against the autocrat, Navalny has aimed to expose Kremlin corruption and malfeasance. While Navalny’s ultimate goal seems to be to take Putin’s place, not just depose him, few believe he will actually succeed. Still, his campaign has inspired tens of thousands across the country to take to the streets to express their frustration with the regime — many for the first time — posing an existential threat to Putin. The problem for the president is, try as he might, he can’t keep the 44-year-old dissident quiet. Last year, Kremlin operatives tried to assassinate the opposition leader with a highly toxic nerve agent planted in his underwear, a bold operation that most experts say likely would have required Putin’s approval to launch. Navalny lived, but he spent five months recuperating from a coma in Germany. Yet despite being threatened with immediate arrest upon arrival back in Russia, he vowed to return to his homeland to continue the fight against Putin. Navalny met that fate on January 17 shortly after his flight from Berlin landed in Moscow, and he’s now imprisoned for at least 2.5 years. But even that attempt to silence Navalny hasn’t worked so far: Navalny has remained in the headlines even while in custody. He started a hunger strike on March 31, protesting the lack of medical care he said he’d received while in prison, and his lawyers continued to publicize his plight throughout his ordeal. His condition had gotten so bad that not even Russian authorities could ignore it. They transferred Navalny to a hospital earlier this week for treatment, though questions remained about the quality of care he’d get. Navalny’s aides were concerned that the pro-democracy leader was on death’s door. “Alexei is dying… it’s a question of days,” Navalny’s spokesperson, Kira Yarmysh, said on Facebook this week. Physicians close to Navalny made the same case, leading the dissident to end his hunger strike on Friday. But Navalny claimed victory in an Instagram post, saying pressure his supporters placed on the regime led independent doctors to check on his condition. “Doctors, whom I fully trust, published a statement yesterday stating that you and I had achieved enough for me to end the hunger strike. And I will say frankly — their words that the tests show that ‘in a minimum time there will be no one to treat…’ seem to me worthy of attention,” he wrote. However, he added that he’s “losing sensitivity” in sections of his arm and legs and still wants to know “what it is and how to treat it.” What happens to Navalny going forward is a serious matter of international concern, with US national security adviser Jake Sullivan recently promising “ there will be consequences ” if the Putin opponent dies in prison. Putin is now on the defensive. He’s receiving calls from President Joe Biden and other leaders to release Navalny, even as Russian authorities round up members of the dissident’s team and family. He’s also under pressure at home from Russians who support Navalny. “Putin was an untouchable, a god above everything else. But that’s no longer the case,” Maria Snegovaya, an expert on Russian politics at George Washington University, told me. Putin broke an implicit promise to Russians. Activists pounced. Little initially bothered Putin after he became president for the first time in 2000. The economy doubled and living standards rose during his first decade in charge, muting critiques from dissidents of the regime’s repression of free speech and civil rights. Experts say Russians implicitly understood there was a grand bargain: If Putin could keep the money flowing and not act in an openly corrupt way, then the citizenry would abide by his iron-fisted leadership. But two events in 2011 ended the fragile deal. First, Putin that September announced he would reassume the presidency after serving one term as Russia’s prime minister, the No.2 role. Simply put, Putin was still in charge of the country, but he accepted a technically inferior position to keep up democratic appearances. The president, Dmitri Medvedev, was viewed as little more than a puppet. By effectively stating “I will be president again” — without giving Russians any real say in the matter — Putin defied the unspoken “don’t be openly corrupt” rule. Second, Putin’s party, United Russia, got caught rigging the December 2011 legislative elections. Fraud in Russian elections was normal, and there wasn’t more than usual during that particular vote, “but examples of fraud were spread quickly on the internet for the first time,” said Timothy Frye, a Columbia University professor and author of the forthcoming Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin’s Russia. That provided ammunition to a growing cadre of opposition activists looking for a catalyzing cause — Alexei Navalny among them. Who is Alexei Navalny? Navalny, who grew up about 60 miles southwest of Moscow, made his name in 2008 as a blogger. His earliest posts centered on corruption at state-owned companies, and sometimes he’d get extraordinary access by becoming a minority shareholder in the company in order to ask probing questions. His readership grew, and his platform turned him into one of the main leaders of the 2011 protests in Moscow. Featuring roughly 50,000 people, they were the biggest in the capital city since the fall of the Soviet Union. “I’d like to thank Alexei Navalny,” a young activist shouted in a room of organizers the day before demonstrations began. “Thanks to him, specifically because of the efforts of this concrete person, tomorrow thousands of people will come out to the square. It was he who united us with the idea: all against ‘the Party of Swindlers and Thieves.’” Navalny rode that wave of popularity to a run for Moscow’s mayor in 2013. It’s more than a prestigious municipal job; whoever runs the capital is viewed by many in Russia as a future top federal official. To win the election, then, would mean more than just getting to lead a global city. It’d mean Navalny was clawing his way into Russia’s inner circle of power. Navalny ran on an unapologetically nationalist platform, most notably calling for restrictive immigration policies to keep Muslims from the Caucasus and Central Asia out of the country and supporting Russia’s 2008 war in Georgia. Duke University’s Irina Soboleva told me that the candidate’s hardline stances during the campaign alienated members of Navalny’s young, urban base. “I consider Aleksei Navalny the most dangerous man in Russia,” Engelina Tareyeva, who worked with Navalny in a Russian liberal party until he was expelled from it in 2007, wrote of him.

Start

United States

USA — Criminal Alexei Navalny, the Russian dissident challenging Putin, explained