Both China and the U.S. have profited from Beijing’s state violence.

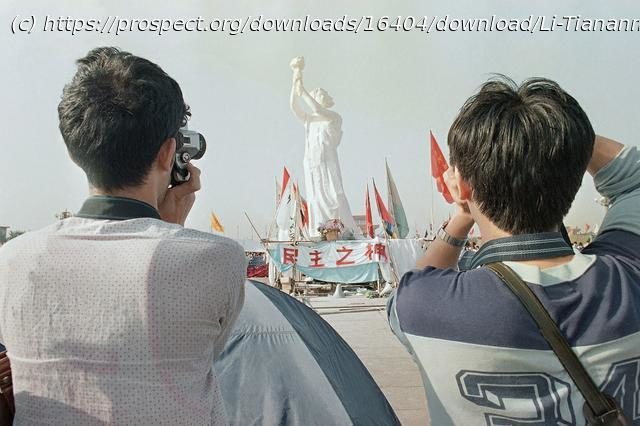

Thirty-two years ago, the Chinese government began its crackdown on democracy demonstrations in Beijing. Though rarely discussed in the U.S., the legacy of June 4, 1989, is all around us. The start of China’s democracy protests shared much with 2020’s summer of protest in response to George Floyd’s murder. In 1989, rallies erupted for weeks in urban centers throughout China, from the far reaches of the northwest in Xinjiang to the southern coastal province of Fujian. Young people led demonstrations that were joined by wide swaths of the public. In Beijing, over a million people would gather in Tiananmen Square, providing food and supplies during a mass hunger strike of around 2,000 demonstrators. Tens of thousands of residents would amass on the highways to block military vehicles from entering the city after martial law was declared. It’s important to recall that workers across China were major participants in the demonstrations. They organized human blockades and pickets, and many joined Workers’ Autonomous Federations that arose in different cities across China that spring, adding their voices to the call for democratic reform. They demanded self-representation through independent labor unions—an expression of what meaningful democracy would look like applied to their own lives. Chinese leaders viewed the spontaneous emergence of organized worker support for the movement as an essential threat. The working class would bear a significant portion of the fatalities in the crackdown and some of the harshest punishments in its aftermath. The state-sponsored repression of Chinese worker rights over the last three decades has likely contributed to the rise in inequality in both China and the U.S. Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping decided to extinguish the threat of independent popular protest with brutal, indiscriminate violence that would go on to shape the conditions of China’s modernization and economic opening. In the rapidly developing economy of the following decades, investors and factory managers had their way paved by public-security officials who would readily threaten, assault, and imprison workers with complaints about, for example, labor conditions, unpaid wages, or workplace injuries.