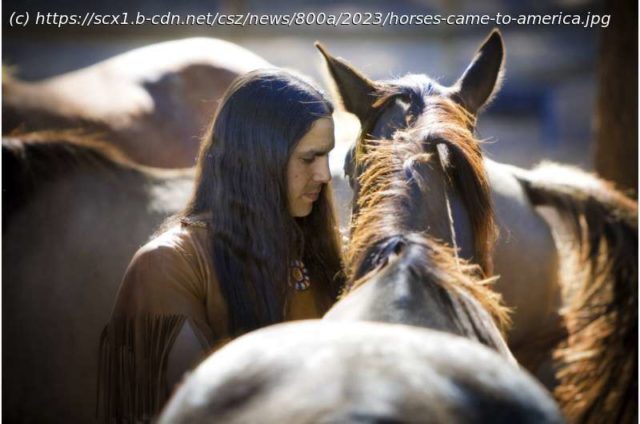

The horse is symbolic of the American West, but when and how domesticated horses first reached the region has long been a matter of historical debate.

The horse is symbolic of the American West, but when and how domesticated horses first reached the region has long been a matter of historical debate.

A new analysis of horse bones gathered from museums across the Great Plains and northern Rockies has revealed that horses were present in the grasslands by the early 1600s, earlier than many written histories suggest.

The timing is significant because it matches up with the oral histories of multiple Indigenous groups that recount their peoples had horses of Spanish descent before Europeans physically arrived in their homelands, perhaps through trading networks.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Science, involved more than 80 co-authors—including archaeologists and geneticists, as well as historians and scientists from the Lakota, Comanche and Pawnee nations.

Prior genetic research has shown that the ancestors of horses first evolved in North America millions of years ago, before making their way to the central plains of Europe and Asia, where they were domesticated. But those early horse ancestors disappeared from the American archaeological record around 6,000 years ago.

In the new study, scientists examined about two dozen sets of horse remains from sites ranging from New Mexico to Idaho to Kansas to establish that horses were ridden and raised by Indigenous groups by the early 1600s.

„Almost every aspect of the human-horse relationship is manifest in the skeleton in some way,“ said University of Colorado at Boulder archaeologist William Taylor, a study author.