The real issue is whether Beijing views the yen’s plunge as a rationale for depreciating the yuan as Chinese growth flatlines.

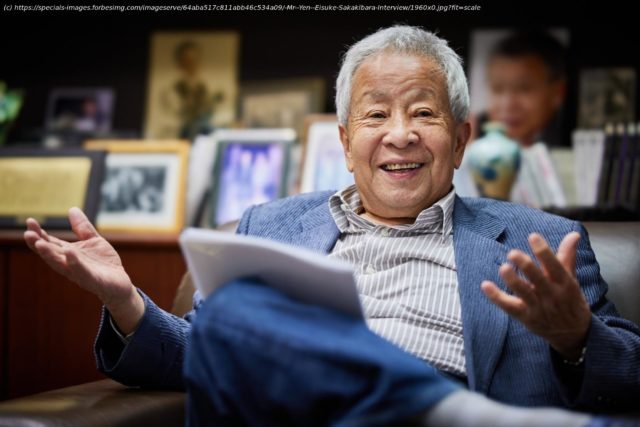

When “Mr. Yen” is back in circulation, look out.

The reference here is to Eisuke Sakakibara, a former 1990s Ministry of Finance official. Mr. Yen, as he’s known, carved out a late-career role as currency market seer. And to my mind, an odd one, given that Sakakibara often seems more of a contrarian indicator.

A decade ago, for example, Sakakibara was insisting the BOJ would be wrapping up quantitative easing and hiking interest rates within a few years. The yen, it followed, would rally. The BOJ has done exactly the opposite—and then some.

Sakakibara is now arguing an already feeble yen could fall another 10%-plus from around 143 to the dollar. On Friday, Bloomberg quoted him as saying: “It might even go beyond 160, maybe next year.” Around there, he notes, Tokyo authorities “may be tempted to intervene to strengthen the yen.”

Yet the real question is what China might be tempted to do, an imponderable Sakakibara remembers all too well from his Finance Ministry days.

As the third-biggest economy, Japan matters plenty in global policymaking circles. For Washington, though, the real issue is whether Beijing views the yen’s plunge as a rationale for depreciating the yuan as Chinese growth flatlines.

China’s 5% growth target is looking less and less attainable as trade headwinds intensify. At home, Chinese leader Xi Jinping is struggling to address record youth unemployment, a shaky property sector, households more enthusiastic about saving than spending and capital outflows as investors seek alternatives.

Abroad, Team Xi faces even higher U.S. interest rates, disappointing demand from Europe and a yen in relative free fall.