Malaria remains one of the world’s deadliest diseases. Each year malaria infections result in hundreds of thousands of deaths, with the majority of fatalities occurring in children under five. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently announced that five cases of mosquito-borne malaria were detected in the United States, the first reported spread in the country in two decades.

Malaria remains one of the world’s deadliest diseases. Each year malaria infections result in hundreds of thousands of deaths, with the majority of fatalities occurring in children under five. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently announced that five cases of mosquito-borne malaria were detected in the United States, the first reported spread in the country in two decades.

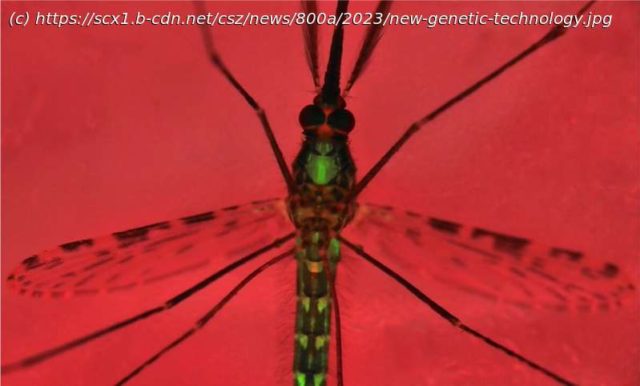

Fortunately, scientists are developing safe technologies to stop the transmission of malaria by genetically editing mosquitoes that spread the parasite that causes the disease. Researchers at the University of California San Diego led by Professor Omar Akbari’s laboratory have engineered a new way to genetically suppress populations of Anopheles gambiae, the mosquitoes that primarily spread malaria in Africa and contribute to economic poverty in affected regions.

The new system targets and kills females of the A. gambiae population since they bite and spread the disease.

Publishing July 5 in the journal Science Advances, first-author Andrea Smidler, a postdoctoral scholar in the UC San Diego School of Biological Sciences, along with former master’s students and co-first authors James Pai and Reema Apte, created a system called Ifegenia, an acronym for „inherited female elimination by genetically encoded nucleases to interrupt alleles.