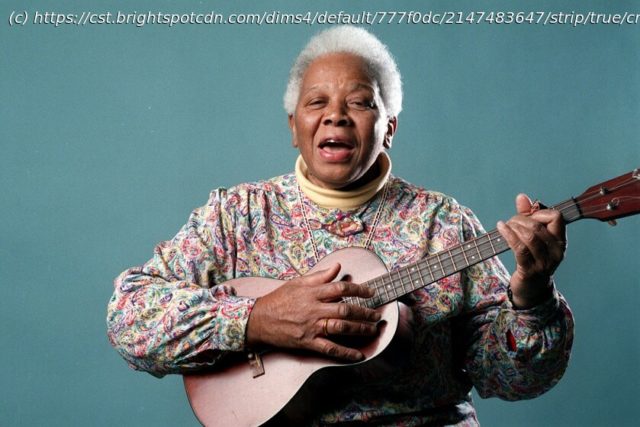

From her town house in Lincoln Park Ella Jenkins traveled the world, performing for generations of kids who never forgot listening to and performing with her. She received a Grammy Award and her music is in the Library of Congress.

Children’s musician Ella Jenkins, who encouraged millions of kids to sing along with her in a career that spanned more than 60 years, has died. She was 100.

Her publicist and friend of 35 years, Lynn Orman, told the Sun-Times she died peacefully on Saturday at a senior-living facility in Chicago. She was surrounded by family and old friends who were playing some of her favorite music, including tunes by Perry Como and Bing Crosby as well as some folk music.

“She forged through to her 100th birthday, there were so many people around her, and she was so excited,” Orman said. “She was just invigorated and empowered by the music.”

For decades, Ms. Jenkins walked out of her townhouse in Lincoln Park, instruments in hand, and traveled the city, state, country and world, singing to children, recording more than 40 albums and teaching her call-and-response-style folk music.

She’s been called the First Lady of Children’s Music, received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy Award and saw her work immortalized in the Library of Congress.

“You would’ve thought she was Elvis,” Orman said of how she was treated by celebrities like Tony Bennett when she received her Grammy in 2004.

“You bring people back to their childhood, and simplicity and the humble beginnings, and no matter who you are — I don’t care if you’re a big star — you can relate,” Orman said. “It’s just something that’s very ethereal, and that’s what she brought out in everyone.”

Ms. Jenkins was born Aug. 6, 1924, in St. Louis but grew up in several places on Chicago’s South Side, including near Washington Park.

Her father worked in a factory; her mother was a domestic worker. They separated when Ella was a child.

Her mother was concerned enough about money that if someone dropped a morsel of food, she would pick it up, brush it off and say, “That didn’t fall. It only stumbled.”

Ms. Jenkins said her mother was a “very fine” cook, ferociously clean, and had refined tastes through her exposure to wealthy homes.

As a child, Ella began experimenting with sounds.

“I got interested in percussion — tapping on tin cans, boxes, knees. I sang. I whistled. Though, `Girls don’t whistle,’ my mother told me,” she told the Sun-Times in 1996.

Ms. Jenkins loved hearing her uncle, a steelworker, play the harmonica. She was inspired after seeing Cab Calloway perform to create call-and-response music.