Why an artwork’s past provenance, owners, secrets, and journey can be just as vital as the artwork’s present

In the high-stakes world of art, authentication and provenance aren’t mere formalities but pillars used to guide value and guard legitimacy. Provenance is always more than a certificate of authenticity or a name on the back of a frame, but the accumulated history of a piece: where it has been, who has loved it, and what lives it has touched.

Sometimes, the journey of an artwork can be as compelling as the art itself. Consider “Salvator Mundi,” attributed to Leonardo da Vinci, which vanished for decades before resurfacing in a small Louisiana auction in 2005. It then ascended to global fame after being acquired by a Saudi prince for $450 million.

Or think of Gustav Klimt’s “Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I,” which was stolen by the Nazis during WWII, then later reclaimed by its rightful heir, an Austrian American Jewish refugee.

While provenance is a strong indicator of taste, its deeper power lies in how it connects people, time, and memory. Behind the sealed glass of museums and the drama of auction houses, a quiet yet formidable discipline sustains the art market and its hierarchies to back this provenance: connoisseurship.

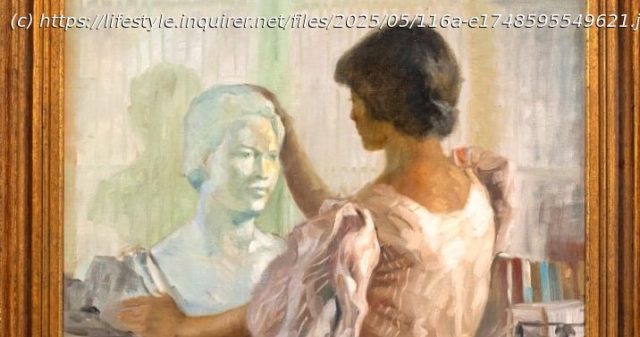

The connoisseur’s eye for taste, trust, and tiny details

At its core, connoisseurship is the ability to discern, through trained observation, the unique touch of an artist. A connoisseur is able to determine how an artist renders forms, textures, or minute anatomical features.

Historically, connoisseurship has been practiced by figures like Giovanni Morelli, Gustav Friedrich Waagen, and Bernard Berenson, whose methodologies shaped the way we judge and assign value to artworks.

Morelli, for instance, developed a near-algorithmic approach: Rather than focusing on grand subjects or expressions, he zeroed in on involuntary stylistic habits, like how an artist draws a fingernail, a curl of hair, or the folds in a sleeve. These micro-details, he argued, were more reliable than signed names, making this “Morellian method” a kind of forensic science.

Berenson, his disciple, infused this with something more psychological.