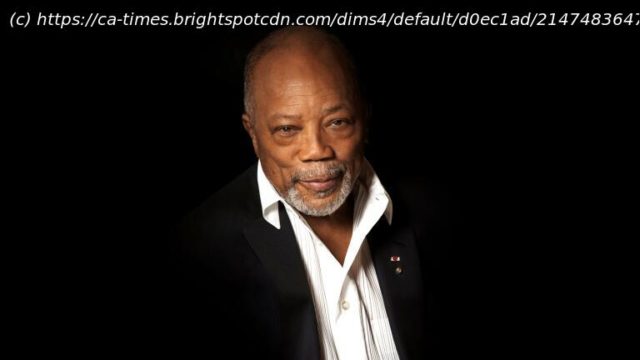

The late Quincy Jones’ life spanned the entirety of modern American pop music — a tradition he absorbed, influenced and reinvented for generations.

The late Quincy Jones’ life spanned the entirety of modern American pop music — a tradition he absorbed, influenced and reinvented for generations. It’s remarkable to look back on the composer, arranger and producer’s life and hear him speak on his friendships and work with Sidney Poitier, Lena Horne, Ella Fitzgerald, Stevie Wonder, Michael Jackson and Tupac Shakur, among hundreds more.

Over the years, The Times spoke to Jones — who died Sunday at 91 — at many junctures in his career, where he recalled being a Black composer in Hollywood in a less-enlightened mid-century climate; making perhaps the biggest pop album of the century with Michael Jackson, and his heartbreak over gangsta rap’s real world violence that touched his family.

Jones’ philosophy on music was cosmopolitan and curious from the start. He traveled widely, and as a composer, he learned from European classical and folk traditions, pairing them with the innovations of Black art forms like American jazz.

Traditional music “enhances your soul,” he told The Times in 2001. “Because you see that most countries, the evolution of their music is based on the roots of their folk music, like ours is. [Béla] Bartók came out of Hungarian folk music. The Scandinavian folklore is awesome. All those tunes that Miles [Davis] and Stan Getz played, ‘Dear Old Stockholm,’ beautiful folk music, you can’t believe how beautiful it is. Traveling is the best education there is. You’re experiencing their food that they like to eat and their language and their music. And that’s the soul. That’s the real stuff. They would tell us: Don’t go to the souk [a marketplace or bazaar]! Don’t go to the casbah! That’s just where we went. That’s like going to the ‘hood! I’m right up in there in a minute, baby.”

Jazz, one of his first loves, imbued everything he did in film scores, pop and education. “[Count] Basie, Clark Terry, it was an amazing education,” he said. “I talk a lot now. But I used to sit down and shut up and listen to them. Because old people know what they are talking about, they’ve been there. All of the young brothers that call Louis Armstrong a ‘Tom’ and all that stuff. This is the man who invented our music. He had no samples, he has no radio station or nothing to listen to. He’s just inventing it. Art Blakey told Branford Marsalis, ‘We had to take a lot so you can do your little flip stuff.’ It’s true. There is a lot of blood out there.”

“Before I die, I want to be a part of a way for Americans to know their own music,” he added. “They don’t get it. We’ve got the greatest mother ship on the planet. We’ve got to talk to the administration. We need a minister of culture — I don’t want to do it, but we need one. Everyone’s got one. This country’s culture is the Esperanto of the world. It’s the first thing that they cut from schools, but if they had it, [there] would be a better spirit in the country.”

Jones came to early renown as a film composer, where he wrote the scores to Oscar-winning “In the Heat of the Night,” “The Wiz,” “In Cold Blood” and “The Color Purple,” among many others.