Careful measures will be important for containing the side effects, allowing the economy to slow at a measured pace for the remainder of this year

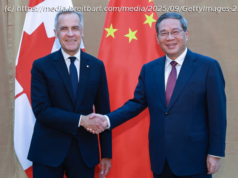

After a solid start to the year, the Chinese economy appears to be coming off the boil. April’s purchasing managers’ index data pointed to some nascent signs of an economy losing momentum after the stellar performance in the first quarter. Both the official and Caixin measures eased back from their multi-year highs, with sub-components showing a broad-based slowdown in domestic and external demand. The upcoming April activity data will likely corroborate the PMIs, registering a sequential deceleration in growth. To be sure, the Chinese economy is not about to fall off a cliff. Far from it, manufacturing and services-sector activities, as indicated in the PMIs, are still growing at a respectable clip. What’s more, a favourable rebalancing of growth from upstream/large enterprises to downstream/small companies appears to be taking shape. This can help to support a further recovery in private-sector investment and make growth less reliant on official stimulus. On the price front, a further retreat in both input and output prices of the PMIs suggests an easing of inflationary pressure. Such a move is consistent with the recent declines in global commodity prices, and regulatory tightening domestically on commodity speculation, driving down prices of iron ore and other raw materials. For upstream mining companies, these price declines will weigh on their bottom line, but downstream users of the commodities will see their profitability expanding on the back of a lower cost of production. This could be one explanation for the diverging performance between the large and small enterprises in the PMIs. For the central bank, tepid price pressure means that broad-based monetary tightening remains some time off. Still, the People’s Bank and China and its peer regulators have continued to rein in financial speculation and leverage. After guiding the interbank interest rates higher and tightening macro prudential regulation, the regulators, particularly the China Banking Regulatory Commission, China’s pre-eminent banking regulator, have further tightened banks’ inter-financial-institution business, including outsourcing asset management and those relating to off-balance-sheet wealth management products. Banks have reacted to these moves by trimming risk exposure, boosting liquidity, and, where possible, shoring up capital positions. The collective decision to de-risk has triggered a tightening of interbank liquidity, driving up market interest rates and long-term bond yields. Credit spreads have also widened, and equity markets declined as financial institutions offloaded risky assets. The Shanghai and Shenzhen composite indices, for example, have declined by 6 to 7 per cent from their highs in early April, while the ChiNext index, which consists of mid- and small-cap stocks, has fallen even more. Chinese equities have underperformed their peers in Asia and the wider emerging market over the past month. It is still early days to assess the full impact of this financial tightening. But a trade-off between the long-run benefits and short-term costs is in the offing. By initiating these measures, Beijing is aiming to reshape the financial system to make it less risky (with reduced leverage) , less speculative (with reduced shadow banking) and more attentive to the real economy. However, achieving these benefits will not be easy: it requires a skillful manoeuvre by the authorities, and it takes time for the results to transpire. For now and the immediate future, the cost of this policy tightening will likely dominate the market and determine how far the authorities may go with the operation. Besides the aforementioned market impact, the real economy will likely feel the pain from higher funding costs and tighter liquidity, too. Already, corporate bond issuance has fallen in recent weeks, and credit growth has slowed. Shadow banking defaults and other credit events may rise as a result, further hurting investor sentiment and banks’ appetite to lend. Overtightening is, therefore, not a trivial risk, and needs to be carefully managed in this year of leadership transition. With downside risks looming, Beijing will likely proceed with caution. The key to a successful deleveraging is not how to prick the bubble, but how to manage the collateral damage afterwards. In this regard, the Chinese authorities have sharpened their skills in managing the negative spillovers from many bubble-bursting exercises in recent years — the interbank liquidity crunch in 2013, the equity market crash in 2015, and a few in commodity and property markets. A careful management of the process, like those in past episodes, will be important for containing the side effects, allowing the economy to slow at a measured pace for the remainder of this year. However, for the sectors that are directly targeted by the regulatory tightening – shadow banking and certain parts of the capital market – pain will be borne and some casualties are inevitable. For investors, selectivity will therefore be paramount for a successful 2017.