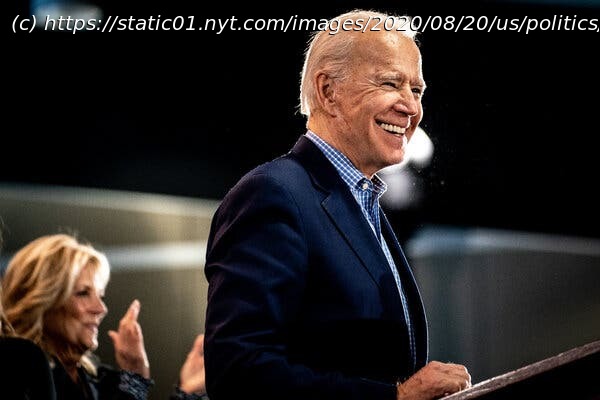

More than three decades after his first presidential run, in the midst of a deadly pandemic and without his son Beau at his side, the former vice president has met his moment.

Joe Biden tells funny stories at funerals and sad ones at campaign stops. He has been running for president long enough to lose the 1988 Democratic primary as a hard-charging 40-something pushing generational change and to win the 2020 primary as the white-haired statesman who knows from sorrow — who can sniff it out in any room, still, and close in like a pang-seeking missile for the stricken. “He asked if I was OK and gave me a hug,” a cane-shuffling Iowa man, Brian Peters, said last winter, blinking away tears after pledging his support to Mr. Biden on a characteristically misty post-event rope line. “I told him that I would be.” Maybe it had to happen this way, friends say, if it was going to happen at all: After nearly a half-century of public life defined most viscerally by the forced commingling of politics and personal loss, the tint of the moment at last matches Mr. Biden’s own story: shadowed by despair, sustained by faith — in himself; in God; in the human capacity for resilience, founded or not. “We all are an accumulation of our life’s experiences,” said Joe Riley, a friend of Mr. Biden’s and the former longtime mayor of Charleston, S. C. And Joseph Robinette Biden Jr.’s experiences have delivered him here. He will at last accept the Democratic presidential nomination, winning the chance to face President Trump because he is, admirers say, all the things that the incumbent is not: empathetic, dependable, decent. There is some irony, Democrats concede, in the idea that Mr. Biden prevailed because voters found him comforting and familiar. Through his years in presidential politics, his longevity has instead generally served to remind his skeptics of all they believe he has gotten wrong: He voted to authorize the use of military force in Iraq and came to regret it. He presided over the committee that subjected Anita Hill to demeaning and invasive questioning in the Supreme Court confirmation hearings for now-Justice Clarence Thomas. He helped craft tough-on-crime legislation that many criminal justice experts now associate with mass incarceration. In this primary campaign, Mr. Biden,77, could often appear almost willfully out of step with the times, telling debate viewers to keep their record players on at night for children’s educational purposes and warmly remembering his relationships with segregationist senators. He won anyway. He is stepping to the lectern on Thursday having reached the precipice of a prize he has chased for more than three decades and talked about since grade school. Yet like many flashes of triumph in his long career, this one is not as he imagined it, the would-be jubilation laced with an abiding gravity. His speech will skew sober, allies say, befitting the national mood. He will not have a large crowd to cheer him in person, in deference to the pandemic that has overwhelmed the nation he hopes to lead. He will not have Beau Biden, his son and political heir, who died in 2015 while pleading with his father not to withdraw from the public arena. “Beau should be the one running,” Mr. Biden said in January, choking up in a television interview. But then, the “should” constructions have never much cooperated in Mr. Biden’s arc, where the bitter and the sweet tend to find each other in metronomic succession. His underdog Senate victory in 1972, as a relentless 29-year-old who did not know better, came a month before the car crash that killed his wife and daughter and injured his two sons, the trauma that forever enshrined him as an avatar of bereavement in the public consciousness.