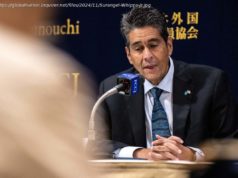

Claudia Mo on the solidarity protest and what comes next.

The pro-democracy opposition in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council resigned en masse last week, a powerful show of solidarity against Beijing’s latest intervention in the territory. The protest came after the Chinese government passed a new law that would disqualify legislators for “unpatriotic” behavior — things like supporting Hong Kong’s independence or colluding with foreign powers. The Hong Kong government quickly expelled four members of the legislature under the new rule: Alvin Yeung, Dennis Kwok, Kwok Ka-ki, and Kenneth Leung. It was the latest attempt by the Chinese government to crush the pro-democracy opposition, this time directly within Hong Kong’s political structures. Which is why the remaining pro-democracy camp all walked out: better to stand in solidarity than to be picked off and disqualified, one by one. The battle in the Legislative Council, or LegCo, comes just months after China imposed a stifling national security law that gave Beijing sweeping powers to crack down on dissent in Hong Kong under the broad categories of “secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security.” That was a direct response to a year of massive pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, which China saw as a threat to its power. Many inside and outside Hong Kong saw the national security law as a “death sentence” for “one country, two systems” — the principle that grants Hong Kong a degree of autonomy and democratic freedom until 2047. Ultimately, the national security law achieved what Beijing wanted: accelerating China’s control of Hong Kong. The law, along with pandemic restrictions, has chilled the protests. And now China has taken yet another step, targeting lawmakers who oppose Beijing from their elected positions. The pro-democracy camp had already been the minority in the LegCo; it could filibuster and delay but ultimately couldn’t block any legislation. Their absence now removes any doubt about what the Hong Kong government has become: another rubber stamp for Beijing’s agenda. I spoke to Claudia Mo, one of the pro-democracy legislators who resigned in protest. She explained the decision, what this means for Hong Kong, and why she and others are still fighting against increasingly impossible odds. Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below. I guess a good place to start would be the news that four pro-democracy legislators were ousted from the Legislative Council last week. This was under a new rule passed by Beijing targeting “unpatriotic” lawmakers, is that right? The order, essentially, is the final, the very ultimate crackdown on Hong Kong’s opposition. It basically says if you are found “unpatriotic” — things that are disliked by the powers that be in Beijing — you’re out. You’re not allowed to stay within the power structure in Hong Kong. So that’s it. That’s the very final nail in the coffin of “one country, two systems.” Beijing keeps reminding us that Hong Kong is part of China, and that it has sovereign power over Hong Kong. True, of course, yes. China has the sovereign power here; we always acknowledge that. But we thought we had “one country, two systems,” and we should have plenty of room, if not wiggle room, to mind our own business and retain Hong Kong’s identity. You say that this is the “final nail in the coffin of the ‘one country, two systems.’” We said that a lot during the summer as China imposed its new national security law on Hong Kong. What makes this particular law even more dangerous to “one country, two systems”? The national security law is all-encompassing. It applies to everyone, right? Just watch out. Whatever you do or say, guard your words, and so on. But this latest Beijing order doesn’t mention anything about the national security law. I suppose Beijing didn’t want to use the national security law against the four legislators, because they didn’t want to make it too clear that the security law is some sort of political weapon. This time, they only stressed the fact that these people have disrespected the mother country’s authority and have worked against the power of the sovereign authorities, and thus should be chucked out. This is specifically targeted at Hong Kong’s political elections. I see. Was there an expectation that China would make a move like this and, as you say, target politicians and the political structure? The democracy camp in Hong Kong as a whole has been expecting something to this effect, so it’s not that we were completely caught by surprise. It’s not surprising, but it’s still shocking because of the extent of this order.