He held the most celebrated record in sports for more than 30 years.

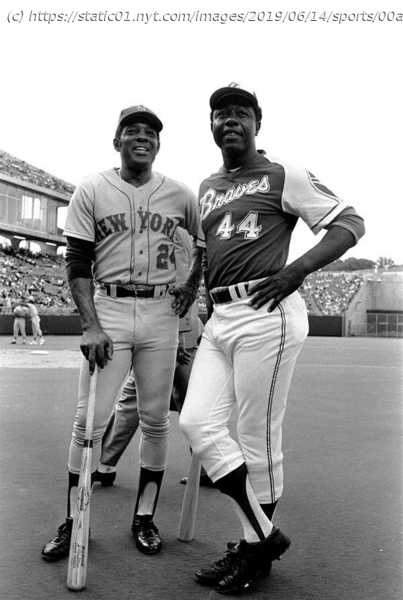

Hank Aaron, who faced down racism as he eclipsed Babe Ruth as baseball’s home run king, hitting 755 homers and holding the most celebrated record in sports for more than 30 years, has died. He was 86. The Atlanta Braves, his team for many years, confirmed the death on Friday in a message from its chairman, Terry McGuirk. No other details were provided. Playing for 23 seasons, all but his final two years with the Braves in Milwaukee and then Atlanta, Aaron was among the greatest all-around players in baseball history and one of the last major league stars to have played in the Negro leagues. But his pursuit of Ruth’s record of 714 home runs proved a deeply troubling affair beyond the pressures of the ball field. When he hit his 715th home run, on the evening of April 8, 1974, against the Los Angeles Dodgers at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, he prevailed in the face of hate mail and even death threats spewing outrage that a Black man could supplant a white baseball icon. The San Francisco Giants’ Barry Bonds surpassed Aaron’s home run record in August 2007 and went on to hit 762 homers. But many inside baseball and out considered Bonds’s achievement to be tainted by suspicions that he had used performance-enhancing drugs in what came to be known as baseball’s steroid era, when bulked-up players achieved stunning feats of slugging. Aaron did not speak out on steroid use, but he declined to follow Bonds around the league to witness his 756th home run. When it came in San Francisco against the Washington Nationals, Aaron limited himself to a message on the stadium’s video board: “My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dreams.” Aaron was routinely brilliant, performing with seemingly effortless grace, but he had little flash, notwithstanding his nickname in the sports pages, Hammerin’ Hank. He long felt that he had not been accorded the recognition he deserved. He played for teams far beyond the news media centers of New York and the West Coast, and his Braves won only two pennants and a single World Series championship, those coming long before he approached Ruth’s record. Aaron did not enjoy the idolatry accorded the Yankees’ Mickey Mantle or match the exuberance and electric presence of the Giants’ Willie Mays, his outfield contemporaries and rivals for acclamation as the greatest ballplayer in major league history. But when he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, his first year of eligibility, Aaron received 97.8 percent of the vote from baseball writers, second at the time only to Ty Cobb, who was inducted in 1936. Aaron grew up in Alabama amid rigid segregation and its humiliations, and he faced abuse from the stands while playing in the South as a minor leaguer. Years later, he felt that Braves fans were largely indifferent or hostile to him as he chased Ruth’s record. And the baseball commissioner at the time, Bowie Kuhn, was not present when he hit his historic 715th home run. All that, and especially the hate mail that besieged him, seared Aaron for years to come. As the 20th anniversary of his home run feat approached in the early 1990s, he told the sports columnist William C. Rhoden of The New York Times, “April 8, 1974, really led up to turning me off on baseball.” “It really made me see for the first time a clear picture of what this country is about,” he said. “My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ball parks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.” Aaron’s achievements went well beyond his home run prowess. In fact, he never hit as many as 50 homers in a single season. He was a two-time National League batting champion and had a career batting average of.305. He was the league’s most valuable player in 1957, when the Milwaukee Braves won their only World Series championship. He was voted an All-Star in all but his first and last seasons, and he won three Gold Glove awards for his play in right field. Aaron combined with the Hall of Fame third baseman Eddie Mathews for 863 home runs during their 13 years together on the Braves, the most ever for two teammates. Aaron remains No.1 in the major leagues in total bases (6,856) and runs batted in (2,297); No.2 in at-bats (12,364), behind Pete Rose; and No.3 in hits (3,771), behind Rose and Cobb. He won the National League’s single-season home run title four times, though his highest total was only 47, in 1971. Matching his jersey number, he hit exactly 44 home runs in four different seasons. At six feet tall and 180 pounds, Aaron was hardly the picture of a slugger, but he had thick, powerful wrists, enabling him to whip the bat out of his right-handed stance with uncommon speed. “He had great forearms and wrists,” Lew Burdette, the outstanding Braves pitcher, recalled in Danny Peary’s oral history “We Played the Game” (1994). “He could be fooled completely and be way out on his front foot, and the bat would still be back, and he’d just roll his wrists and hit the ball out of the ballpark.” Aaron was quick on the bases and in the outfield. “There aren’t five men faster in baseball, and no better base runner,” Bobby Bragan, Aaron’s manager in the mid-1960s, told Sports Illustrated. “If you need a base, he’ll steal it quietly. If you need a shoestring catch, he’ll make it, and his hat won’t fly off and he won’t fall on his butt. He does it like DiMaggio.” Aaron was a keen student of pitching and kept himself in excellent shape. “I concentrated on the pitchers,” he said in his memoir, “I Had a Hammer” (1991, with Lonnie Wheeler). “I didn’t stay up nights worrying about my weight distribution, or the location of my hands, or the turn of my hips: I stayed up thinking about the pitcher I was going to face the next day. I used to play every pitcher in my mind before I went to the ballpark.” Dusty Baker, later a longtime manager, was mentored by Aaron when he was a young player with the Braves. “Nobody had concentration like he did, sitting there in the dugout, looking at the pitcher through the little hole in his cap to focus on the release point,” Baker once said. “Never saw anyone do that before Hank.” Baker said Aaron had been hampered by sciatic nerve problems but had the ability to “think away the pain and to condition himself like no other baseball player of his time.” Henry Louis Aaron was born on Feb.5,1934, in Mobile, Ala., one of eight children of Herbert and Estella (Pritchett) Aaron. His father worked in shipyards. His mother joined with her husband in overseeing a close-knit family. She encouraged Henry (he never liked being called Hank, as he would customarily be known on the sports pages) to consider going to college. In March 1948, a year after Jackie Robinson broke the modern major league color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Robinson was in Mobile for a spring training game. Henry Aaron was in the crowd of Black youngsters who had gathered in town to hear Robinson tell them of the possibilities that would be opening to Black people. Robinson spoke of the need to strive for a good education. But Henry, only 14 but already a talented sandlot ballplayer, cared little for his high school studies. He idolized Robinson and envisioned professional baseball as the road to escaping poverty and segregation. While a teenager, he played alongside men many years his senior as a shortstop for the semipro Mobile Black Bears. (Mobile over the years was a breeding ground for top baseball talent, producing Satchel Paige and later the Hall of Famers Billy Williams and Willie McCovey.) He was then signed by the Negro leagues’ Indianapolis Clowns, a barnstorming team that combined entertainment with baseball, much like basketball’s Harlem Globetrotters. After beginning the 1952 season with the Clowns, Aaron was signed in June by the Braves, who were in their last season in Boston. They assigned him to play for their farm team in Eau Claire, Wis., and he was named the Northern League’s rookie of the year that season.