Even the 9/11 Commission soft-pedaled the failures of U.S. leaders and the intelligence community.

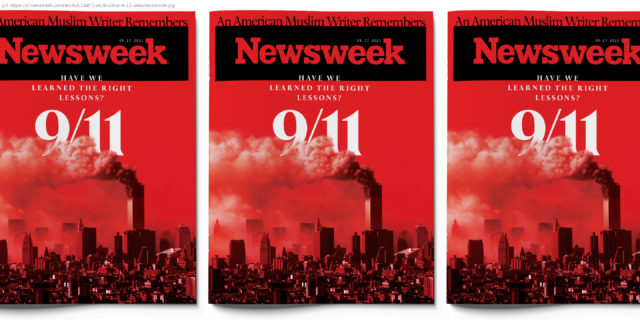

September 11 is the most studied day of our lifetimes. Almost everyone who was old enough remembers the details—where they were, how they felt, what it meant to them. It remains unforgettable. The U.S. intelligence community had known some sort of terrorist attack was on the way but failed to focus or to act. After 9/11, there was finger-pointing at President George W. Bush and the White House, between the previous Bill Clinton and Bush administrations, at the CIA, NSA, FBI and even at the Pentagon. The government pledged to do better: to break down barriers to intelligence analysis and sharing, and to organize itself so that such a catastrophic event would never happen again. But even in the immediate aftermath there were more powerful emotions that overshadowed the desire for reform. The desire for revenge propelled the administration of George W. Bush to declare a global war. Panic within the government drove the secret agencies to take their own liberties—through warrantless surveillance, torture and secret prisons, arbitrary watch listing, domestic spying and more. And though reforms did follow, including the largest reorganization of government in 50 years, government performance again faltered. September 11 was followed by other intelligence debacles, from the faulty reports regarding Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction to the botched withdrawal from Afghanistan last month: a long line of failures that yearn for accountability. Polls show that a majority of Americans remain bewildered about the attack, the perpetrators and the reason. And most everyone laments Washington’s political and partisan machinations and the decline of American institutions. However, few connect today’s national friction to the aftermath of 9/11. Yes, the government has (so far) succeeded in preventing another such attack on U.S. soil, but an even greater disaster in endless war and the collapse of civic life sullies the achievement. And despite legions of blue ribbon panels to review what happened, despite subsequent revelations of wrongdoing, despite administrations promising to do better, the basic reality of government was exposed: No one is held accountable—not a White House official or top government agency director, not an intelligence analyst or FBI agent, not even a lowly airport security screener. The cost of government secrecy has also been exposed. It nurtures our world of alternative facts and undermines public faith in government motivations and authority. Secrecy has also fed a generational gap, with young people indifferent to or confused about national security, an entire new generation seeking their own agendas with regard to what is vital for the country and the world. So yes: We will never forget. But a more interesting question at the 20th anniversary is what we should remember—or more, what should we learn? Tragic failures On September 11,2001, two hijacked commercial airliners crashed into the north and south towers of the World Trade Center. Soon thereafter, the Pentagon was struck by a third hijacked plane. A fourth hijacked plane, bound for the U.S. Capitol building, crashed into a field in Somerset County in southern Pennsylvania after passengers managed to overpower the hijackers. The 19 hijackers were all young Arab men, from four different countries, all sacrificing their lives on behalf of Al-Qaeda. The attacks that day killed 3,030 U.S. citizens and other nationals. There were 2,735 persons who died in the twin towers in New York: 2,184 at work in the buildings,129 aboard the two aircraft (119 passengers and crew, and 10 hijackers),343 firefighters,71 law enforcement officers, and eight private emergency medical technicians and paramedics. A total of 189 were killed at the Pentagon: 125 uniformed military, civilian and contractor personnel in the building and 64 passengers, crew, and terrorists. Forty-four died in Pennsylvania. The day itself was horrific in other ways. Despite spending hundreds of billions of dollars on presidential communications, on nationwide air defenses, on airport security and on emergency preparedness, despite preparations that were supposed to work in the face of a full scale nuclear war, hardly any part of what had been created worked. Leaders were preoccupied with the most basic activities—getting phone calls through, finding and protecting their loved ones, keeping up with the news, struggling with the rumor mill. For a large part of the day, President Bush was unable to reliably communicate or know precisely what was going on. Successors to the presidency and Cabinet members ignored continuity-of-government plans and procedures for emergency response. The White House and Pentagon were out of sync and made decisions without any basis in fact. There was stunning confusion regarding what the president ordered Air Force fighter jets to do and why. The Pentagon confusedly declared a high-level alert—including nuclear forces—with key decision makers, including Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and acting Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Dick Meyers mistaking measures to increase the protection of American forces with an alert that prepared for war. Many of the organizational and technological deficiencies of 9/11 have since been corrected, we’ve been told. But in an age where information overload is exponentially worse, and where cyberthreats raise questions about the reliability and credibility of communications and decision-making, there is no particular reason to believe that the very same issues won’t repeat in some future crisis. And indeed everything that happened 20 years ago recurred in the past two years. With the emergence of COVID-19, continuity and emergency actions again became important when questions of the president and vice president separating were raised, and yet none of the established procedures were followed. And when rioters swarmed the Capitol on January 6th, the lack of preparedness was alarming. Questions of who was in charge again became paramount. The dots were not connected; the information did not flow; the decision-makers were paralyzed. The failure to connect the dots, big and small, was certainly a theme of the 9/11 Commission, which published its final report three years after the attacks. It stated that « the 9/11 attacks were a shock, but they should not have come as a surprise. Islamic extremists had given plenty of warnings that they meant to kill Americans indiscriminately and in large numbers. » But it’s worse than that. As early as 1995, when a plot was foiled in the Philippines, the CIA knew of plans to use airplanes in an attack. And though an August 6th President’s Daily Brief (PDB) became infamous as the warning that was ignored, an item in the December 4,1998 PDB titled « Bin Laden preparing to hijack U.

Home

United States

USA — Financial After 9/11, No Americans Were Held to Account. Here's Why That's Dangerous