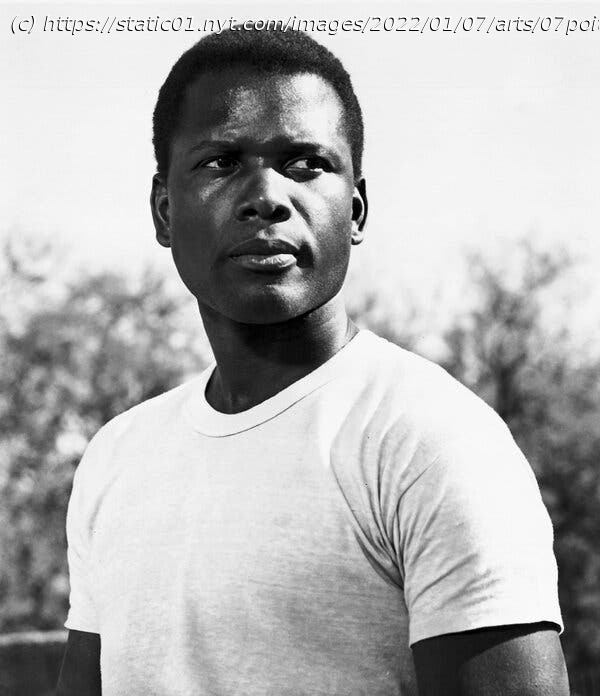

Without the obstacles put in his way, he could’ve been even bigger than he was. But Mr. Poitier still managed to be a giant, which, in itself, is astonishing.

Were anyone to ask me who’s the greatest American movie star, my answer would never change. And it will never change because the answer is easy. The greatest American movie star is Sidney Poitier. You mean the greatest Black movie star? I don’t. Am I being controversial? Confrontational? Contrarian? No. I’m simply telling the truth. Who did more with less? Of whom was less expected as much as more? Who had more eyes and more daggers, more hopes and fears and intentions aimed his way, at his person, his skill and, by extension, his people? Race shouldn’t matter here. But it must, since Hollywood made his race the matter. Movie after movie insisted he be the Black man for white America, which he was fine with, of course. He was Black. But the radical shock of Sidney Poitier was the stress his stardom placed on “man.” Hu man. Let’s say Mr. Poitier had a good 20-year run as a star, from 1958, when “The Defiant Ones” came out, to 1978, when the last of his hit trilogy with Bill Cosby left movie theaters. He was making just about a movie a year, many of them unmemorable. On one hand, that’s stardom. One the other: Mr. Poitier achieved his greatness partially as a matter of “despite.” He achieved all he did despite knowing what he couldn’t do. I mean, he could’ve done it — could’ve played Cool Hand Luke, could’ve been the Graduate, could’ve done “Bullitt,” could have been Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. There are maybe a dozen roles, capstones, that nobody would have offered to Mr. Poitier because he Wouldn’t Have Been Right for the Part. I believe with all my heart that Mr. Poitier was as crucial in the odyssey of freedom and equality for Black Americans — for personhood — as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, as Martin Luther King Jr. A clear descendant of Douglass’s rhetorical brilliance, he spoke the words of white people but from his own mouth. His projected image begot what is now a galaxy of other Black actors, doing acting as diverse and tiered as a shopping mall. Black artists in this country bear the curious, hilarious burden of history. Their work has to advance; to answer, to question, sit with, and not know. To take on, to risk. To do not only more, but often the most. It must also counteract and dispel; it must un do. Mr. Poitier was American art’s great undoer. In the movies, Black characters were jolly statuary — hoisting luggage, serving food, tending children — meant to decorate a white American’s dream. Acting could be a carceral affair. Mr. Poitier arrived at the start of the civil rights movement, in time to spring the Black image from the prison of the antebellum and minstrelsy eras. He was scarcely the first to try. He just led more people farther down the road than any other artist. Of course, what ensued instead was complicated: a kind of prisoner swap. This undoing business is tricky. The undoer must be both historic and a vessel of history. So Mr. Poitier was accused of being all kinds of Uncle Tom, because the task of undoing has tended to require collaboration with white people.