An analysis of obsidian artifacts excavated during the 1960s at two prominent archaeological sites in southwestern Iran suggests that the networks Neolithic people formed in the region as they developed agriculture are larger and more complex than previously believed, according to a new study by Yale researchers.

October 17, 2022

An analysis of obsidian artifacts excavated during the 1960s at two prominent archaeological sites in southwestern Iran suggests that the networks Neolithic people formed in the region as they developed agriculture are larger and more complex than previously believed, according to a new study by Yale researchers.

The study, published Oct. 17 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is the first to apply state-of-the-art analytical tools to a collection of 2,100 obsidian artifacts housed at the Yale Peabody Museum. The artifacts were unearthed more than 50 years ago at Ali Kosh and Chagha Sefid, sites on Iran’s Deh Luran Plain that yielded important archaeological discoveries from the Neolithic Era—the period beginning about 12,000 years ago when people began farming, domesticating animals, and establishing permanent settlements.

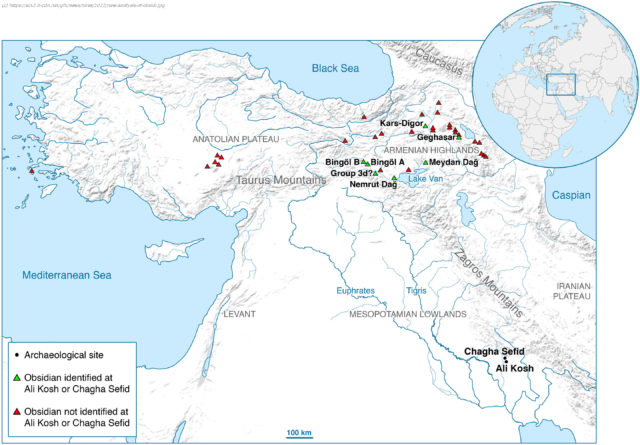

Original analyses performed shortly after the artifacts were discovered had suggested people first acquired the obsidian—volcanic glass—from Nemrut Dağ, a now-dormant volcano in Eastern Turkey, and then relied on an unknown second source for the material. This new elemental analysis showed the obsidian came from seven distinct sources, including Nemrut Dağ, in present-day Turkey and Armenia, which is as far as about 1,000 miles on foot from the excavation sites.

« It wasn’t a simple pattern of people obtaining obsidian from one source and then shifting to the next, » said Ellery Frahm, an archaeological scientist in the Department of Anthropology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and the study’s lead author.