Inspired by a 13th-century Sufi saint, the anthology Naghmat-us-Sama’ by Syed Noorul Hasan has contributed to the persistence of Persian in modern-day music.

Ninety years ago, a pensioner named Syed Noorul Hasan published an anthology of Persian verse titled Naghmat-us-Sama’ (Songs for Listening). A dense book running almost 500 pages, it contained more than 700 meticulously curated Persian poems that he had heard performed at shrines across North India as well as collected from other sources.

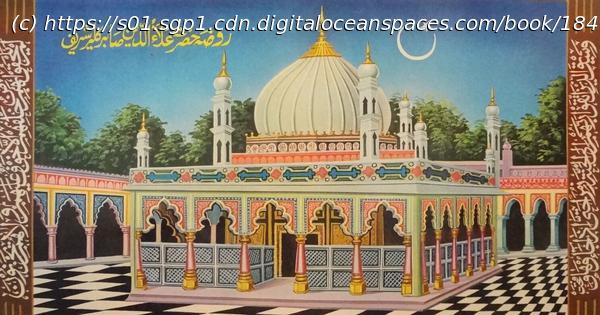

Naghmat-us-Sama’ is dedicated to the memory of a 13th century Sufi, Hazrat Alauddin Sabir Kalyari, a visit to whose shrine at Piran Kaliyar, Uttarakhand, lead to a personal mystic epiphany and inspired Hasan to produce the anthology.

Sama’, a complicated term derived from Arabic, literally means “listening, or hearing”. But is used in a broader context to refer to many forms of ceremonial or religious performance and song, as well as the mental state of ecstasy that this induces in listeners.

Noorul Hasan’s 1935 anthology is an eclectic mix of various forms – ghazal predominantly, but also several other poetic genres, clubbed together with the umbrella term naghma (songs). They were selected somewhat arbitrarily for their musicality, popularity and because they were frequently performed at shrines across North India.

The book contains an extensive, somewhat ponderous, essay on the etiquette governing such musical performance and their permissibility in Islam. It makes no claims to comprehensiveness, accuracy or even credible attribution.

Noorul Hasan’s preface with great candour admits that he collected whatever he could, as he heard it performed, and as shared by scholars such as “Maikash” Akbarabadi. In fact, he even goes on to admit that for several lyrics, he was unable to gather more than three or four verses or find any details about the poets.

The book begins with a Guzarish (request) to his readers, which contains an elaborate lament about the state of Persian in India. He begins:

The Guzarish reflected the reality of his time – a loss of interest and understanding in Persian – one that has only worsened since his compilation. As the ethnomusicologist Regula Qureshi points out, Persian, once the pre-eminent language of sama’, a marker of audience sophistication, and language of high status, had even before the 1970s increasingly fallen out of fashion among patrons, audiences and musicians.

Home

United States

USA — Music How the modern Persian qawwali canon emerged from an Uttarakhand shrine 90...