Christopher Nolan’s biopic traces the rise and fall of American theoretical physicist J Robert Oppenheimer.

Towards the end of Christopher Nolan’s biopic of J Robert Oppenheimer, the American physicist is asked about why his views on the atomic bomb that he helped create changed in a span of a few years. Oppenheimer’s reply is vague, unsatisfactory even. In the same way, the film about him dances around the question that has fascinated as well as plagued Oppenheimer’s admirers.

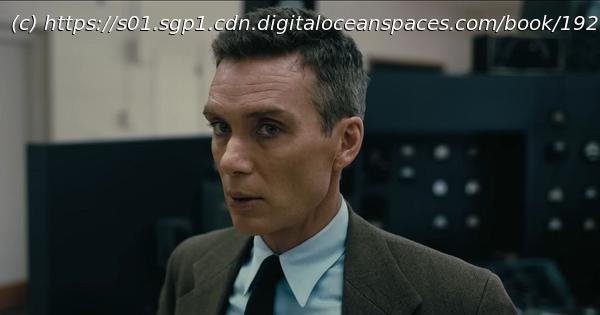

Nolan’s most political film plays out like a 1970s-style conspiracy thriller, in which unfounded suspicions about Communism combine with a narrow definition of nationalism to make a villain out of a hero. A sprawling cast, led by Cillian Murphy as Oppenheimer, lines up for a movie that is grand in vision and grandiloquent in its staging.

Oppenheimer takes off from America’s nuclear bomb programme, codenamed the Manhattan Project, in the early 1940s. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, meant to bring a brutal end to Japan’s continued opposition to the Allied forces during World War II, had tremendous moral consequences, most of all for the man who came to be known as the “father of the bomb”.

The 190-minute film has been adapted by Nolan from the 2005 biography American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J Sherwin. Rather than following a linear narrative that might have more effectively explained Oppenheimer’s fall from grace, Nolan opts for the mangled timelines, breakneck editing pattern and operatic sweep that mark his cinema.

The fragmented approach results in brilliant individual scenes that don’t add up to a composite picture. The extremely busy plot includes Oppenheimer’s formative years, his flirtation with Communism, his leadership of the Manhattan Project, the debates about the proper use of a destructive technology and Oppenheimer’s fraught ties with his wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) and lover Jean (Florence Pugh).