The search for extrasolar planets is currently undergoing a seismic shift. With the deployment of the Kepler Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), scientists discovered thousands of exoplanets, most of which were detected and confirmed using indirect methods.

The search for extrasolar planets is currently undergoing a seismic shift. With the deployment of the Kepler Space Telescope and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), scientists discovered thousands of exoplanets, most of which were detected and confirmed using indirect methods.

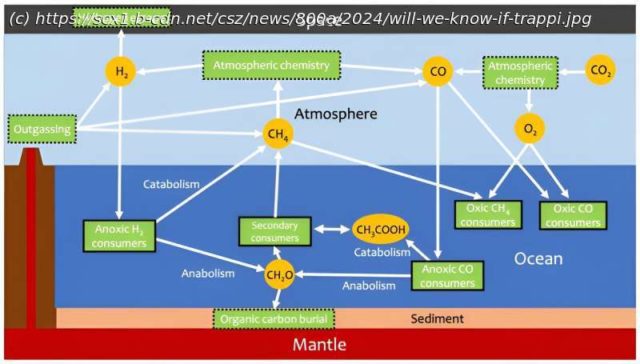

But in more recent years, and with the launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the field has been transitioning toward one of characterization. In this process, scientists rely on emission spectra from exoplanet atmospheres to search for the chemical signatures we associate with life (biosignatures).

However, there’s some controversy regarding the kinds of signatures scientists should look for. Essentially, astrobiology uses life on Earth as a template when searching for indications of extraterrestrial life, much like how exoplanet hunters use Earth as a standard for measuring « habitability. »

But as many scientists have pointed out, life on Earth and its natural environment have evolved considerably over time. In a recent paper posted to the arXiv preprint server, an international team demonstrated how astrobiologists could look for life on TRAPPIST-1e based on what existed on Earth billions of years ago.

The team consisted of astronomers and astrobiologists from the Global Systems Institute, and the Departments of Physics and Astronomy, Mathematics and Statistics, and Natural Sciences at the University of Exeter. They were joined by researchers from the School of Earth and Ocean Sciences at the University of Victoria and the Natural History Museum in London.

The paper that describes their findings, « Biosignatures from pre-oxygen photosynthesizing life on TRAPPIST-1e, » will be published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The TRAPPIST-1 system has been the focal point of attention ever since astronomers confirmed the presence of three exoplanets in 2016, which grew to seven by the following year. As one of many systems with a low-mass, cooler M-type (red dwarf) parent star, there are unresolved questions about whether any of its planets could be habitable. Much of this concerns the variable and unstable nature of red dwarfs, which are prone to flare activity and may not produce enough of the necessary photons to power photosynthesis.

With so many rocky planets found orbiting red dwarf suns, including the nearest exoplanet to our solar system (Proxima b), many astronomers feel these systems would be the ideal place to look for extraterrestrial life.