The completion of the full « telomere-to-telomere » (T2T) human genome last year emphasized that genome sequences that were previously thought to be « complete » were not, in fact, complete at all.

The completion of the full « telomere-to-telomere » (T2T) human genome last year emphasized that genome sequences that were previously thought to be « complete » were not, in fact, complete at all.

Moreover, many recent genomes are sequenced with short-read sequencing technologies, which fragment DNA into short segments, typically 150-300 base pairs long, and are then compared to a reference sequence. While fast, accurate and relatively economical, short-read methodologies routinely miss large parts of the genome, about 10% overall. The missing segments include regions of high G/C content and repetitive sequences, including segmental duplications, simple repeats, and transposable elements (TEs).

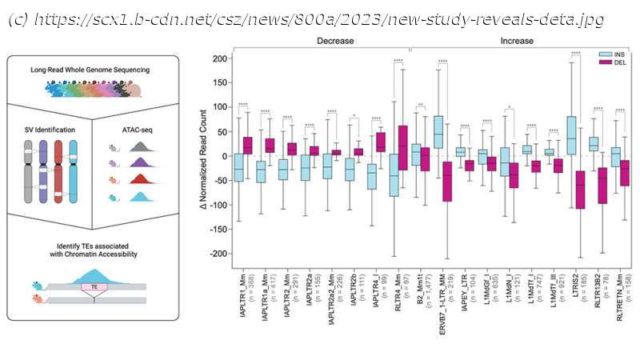

TEs are repetitive sequences that have moved to other locations in the genome, and the mobility of these sequences contribute greatly to genomic variation. Repetitive sequences frequently underlie the formation of structural variants (SVs)- genomic differences resulting from duplications, insertions, deletions, and inversions. SVs are often missed when using short read sequencing (in particular those mediated by repeats) but they can play important roles in genome dysregulation and disease.

Researchers have turned to long-read sequencing to more completely analyze genomes, as these technologies enable sequencing of far longer DNA segments and can accurately capture a more complete picture of a genome. Recent advances have improved long read accuracy and utility, allowing researchers to investigate previously undetected genomic features, and not just in humans.

Jackson Laboratory (JAX) and University of Connecticut Health Center Assistant Professor Christine Beck, Ph.D., led a team that explored the genomes of another notable species, the mouse, and revealed details across 20 diverse inbred strains that will be critical for informing mouse-based genetics and genomics research moving forward.

Mice have their own reference genome, known as GRCm39, based on the sequence of C57BL/6J, a strain from the Mus musculus domesticus subspecies. But many commonly used laboratory mouse strains have been derived from two other subspecies as well, Mus musculus castaneus and Mus musculus musculus, and there are many genetic differences between different inbred strains.

For the work presented in « Resolution of structural variation in diverse mouse genomes reveals chromatin remodeling due to transposable elements, » published in Cell Genomics, Dr.