In Benin’s economic capital of Cotonou, as in many other African cities, finding a house, office or restaurant is often like a treasure hunt.

Luck, if not a miracle, is required as easy clues such as street names, even where they exist, are usually not posted and address numbers are rarely marked.

Most people in Cotonou formulate complex combinations of landmarks and directions to navigate around town.

Typical directions might be: «My office is after the big market, past the apartment block on the right with the mobile phone mast, and it’s the third road on the left, tiled building.»

Can’t see the apartment block with the mobile phone mast? Game over, back to square one.

Sam Agbadonou, a 34-year-old former medical technician, knows how frustrating it can be to get around and describes Cotonou as a «navigation challenge».

«I was called when there were break-downs and went to health centres to repair machines that save lives, » he said.

«But some centres are really in the middle of outlying neighbourhoods and it is difficult to get there.»

Now, to put an end to the hassle and quickly find their destination, locals are turning to crowdsourced mapping applications adapted for use in Africa that are challenging Google Maps for dominance on the continent.

‘Map party’

In 2013, when Agbadonou heard about OpenStreetMap, an international project founded in 2004 to create a free world map, he knew it was a good idea.

Agbadonou founded the Benin branch of the project, which today boasts 30 members.

With his friend Saliou Abdou, a trained geographer, Agbadonou regularly organises «map parties»—field trips to identify the city’s geographical data.

They start with the basics—street names and address numbers—and move on to other details that set their maps apart from the Silicon Valley competition.

«We write down everything: the trees, the water points, the vulcaniser (tyre repairer) on the street corner, the tailor’s shop…. You don’t see that on Google Maps!» Agbadonou said with pride.

Thanks to his work over the last four years, Cotonou is slowly revealing itself.

For example, the Ladji district, which never used to feature on most maps, is now included.

Armelle Choplin, an urban planner at the Institute of Research for Development (IRD) in Cotonou, has no choice but to use Google Maps for her work.

But she is relying more and more on the crowdsourced maps which are more adapted to an African context.

«IGN France (the French national institute of geographic and forest information) carried out an aerial mapping of Benin between 2015 and 2016 and it should be available in September, » Choplin said.

«But we don’t know if we will have access or the terms.»

Social inclusion

Rapid population growth, lack of regulation in real estate and haphazard urbanisation are a headache for most big cities in Africa.

Along the coast in Ghana, Sesinam Dagadu created a similar mobile app called SnooCode, which targets the poorest in society and the illiterate.

His goal is to give «an address for every man, woman and child» by issuing an individual «location code» as a substitute address.

«I wanted to make sure our system was accessible to those at the bottom of the social pyramid, » Dagadu said about his app, which is free.

«Without addresses, many important features of the modern society no longer work, from tracking diseases and emergency response services to e-commerce and deliveries, » said the 31-year-old.

Citizenship

OpenStreetMap is already being used by humanitarian organisations during epidemics.

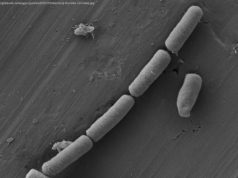

Enthusiastic communities of amateur cartographers participating in ‘mapathons’ have been inputting geographical data from satellite images available on the internet into the online map.

Some have recently focused on the Democratic Republic of Congo, where several cases of Ebola have been reported.

In particularly remote areas of a country, maps only show the outline of roads.

The cartographers add houses and, crucially, water points—essential data to stop the spread of an epidemic.

For volunteers or the app’s creators, map-making isn’t just a passion, it’s become a part of what it means to be a citizen.

As geographer Abdou puts it, working on the maps is his way of «contributing to the development of my country».

Explore further: Google Maps guides travellers offline