Weighing the balance of risks, though, is a shade more challenging when it affects the youngest among us.

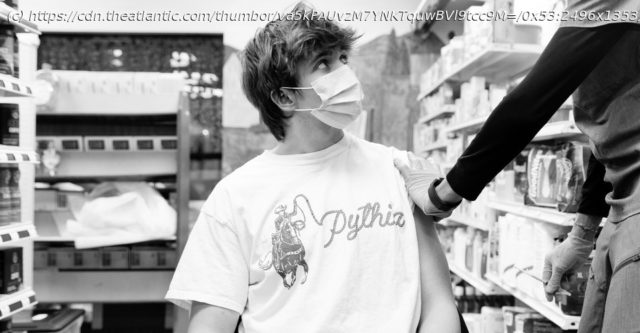

The most reliable way to inflame the heart is to bother it with a virus. Many types of viruses can manage it— coxsackieviruses, flu viruses, herpesviruses, adenoviruses, even the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2. Some of these pathogens bust their way straight into cardiac tissue, damaging cells directly; others rile up the immune system so overzealously that the heart gets caught in the crossfire. Whatever the cause, the condition is typically mild, but can occasionally be severe enough to permanently compromise the heart, requiring lifesaving interventions including ventilators or organ transplants; in very rare cases, it’s fatal. That is decidedly not what we’re seeing in the CDC’s recent reports. The agency has confirmed more than 500 cases of myocarditis or pericarditis—inflammation of the heart itself or of the lining that shrouds it—in people younger than 30 who recently received Pfizer-BioNTech’s or Moderna’s two-shot COVID-19 vaccines. These events are, so far, not matching the most terrifying versions of the condition, which have been observed with coronavirus infections. Rather, compared with more typical cases of myocarditis, the ones linked to the vaccines, on average, involve briefer symptoms and speedier recoveries, even with less invasive treatments. Still, the incidents are showing up in the few days that follow each vaccine’s second dose at higher-than-expected rates, especially in boys and young men, and no one is yet sure why. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, met last week to weigh the risks and benefits of keeping the vaccines in circulation among the nation’s eligible youngest. It rapidly reached a familiar verdict: The perks of immunization far outweigh the potential drawbacks of these side effects and others. Days later, the FDA appended a warning about the rare events onto its fact sheets for the vaccines. Most of the experts I spoke with enthusiastically backed both agencies’ decisions without reservation. Vaccines, they said, remain our most powerful defensive tool against the coronavirus; if anything, staying un immunized is the bigger gamble when it comes to severe organ inflammation. But several of them also noted that this particular side effect, and the country’s response to it, represents a new type of stumbling block for our inoculations. The shots themselves, which are excellent, haven’t changed. But the context in which we’re deploying them has. This potential side effect is the first to concentrate like this in children, who are still relatively new to COVID-19 vaccination. Post-vaccine myocarditis still isn’t well defined; neither are the full consequences of pediatric COVID-19. For more than a year now, the pandemic has forced people to pit a pile of risky unknowns against another pile of risky unknowns, but anything that concerns kids’ health is bound to make tensions run particularly high. A recent Kaiser Family Foundation poll found that recent news of heart problems was a top-of-mind concern for many parents, who are often less likely to vaccinate their children than themselves. The country’s situation is also very different from when the vaccines first arrived. Different types of shots are probably on their way, offering alternative routes to vaccination, perhaps without this particular risk. More versions of the virus are on our doorstep as well, and experts can’t confidently forecast our fates through the fall and winter. We are, once again, engaged in a game of pandemic chess, one that’s not getting much easier over time. We’re still figuring out the pieces we’re handling, and the crafty opponent on the other side; we’re relearning the rules, and the landscape of our board. And this next round, some of the most prominent players are our kids. That the recent cases of post-vaccination myocarditis are relatively mild is, to start, “very reassuring,” said Judith Guzman-Cottrill, a pediatric-infectious-disease physician at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), who helped identify some of the earliest instances of inflammation back in April.