An object that’s intrinsically flat, say a piece of paper, can be shaped into a cylinder without stretching or tearing it. The same isn’t true, however, for something intrinsically curved like a contact lens. When compressed between two flat surfaces or laid on water, curved objects will flatten, but with wrinkles that form as they buckle.

September 11, 2022

An object that’s intrinsically flat, say a piece of paper, can be shaped into a cylinder without stretching or tearing it. The same isn’t true, however, for something intrinsically curved like a contact lens. When compressed between two flat surfaces or laid on water, curved objects will flatten, but with wrinkles that form as they buckle.

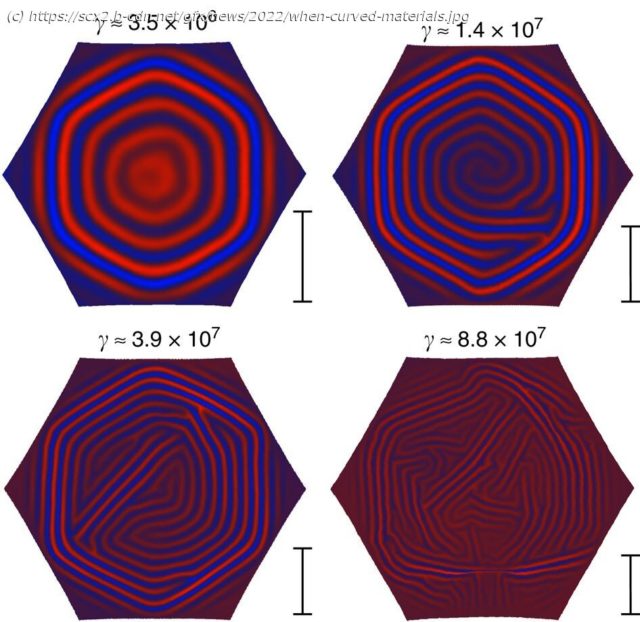

Now, research from the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC), and Syracuse University has shown that with some simple geometry it’s possible to predict the patterns of those wrinkles, both where they will form and in some cases their direction. The findings, published in Nature Physics, have a range of implications, from how materials interact with moisture and reflect sunlight in nature to the way a flexible electronic might bend.

«The beauty of this work is how simple it really is,» says Eleni Katifori, an associate professor in Penn’s Department of Physics & Astronomy. «What’s behind it is very complicated, the physics that’s translated through these rules we found, but the rules themselves are very simple. It’s inspiring.»

Meeting of the minds

Since her Ph.D. work, Katifori has been interested in the mechanics of how thin membranes curve. Though this remained a curiosity, her research path veered toward fluid-flow networks instead. Then, while collaborating on a project with Penn colleague Randall Kamien and then postdoctoral fellow Hillel Aharoni, Katifori observed something she couldn’t explain at the time. «That is, we noticed the wrinkles form in domains,» she says.

In other words, when a curved surface gets flattened, it ends up with excess material and subsequent wrinkles. Those wrinkles emerge in patterns or sectors. «The question became, why do the wrinkles arrange in that way?» says Katifori. «We didn’t understand how important the domains in the wrinkling truly are.»

At a conference in 2016, mathematician Ian Tobasco, an assistant professor at UIC, heard Aharoni give a talk on the subject. «It was the first time I saw this model system being presented,» Tobasco says. «I thought it was really cool.» In mid-2017, Katifori, Aharoni, and colleagues published findings on the subject in Nature Communications, then at a workshop later that year, Tobasco met Joseph Paulsen from Syracuse, who had presented preliminary data on the experimentation his group had done on wrinkles.