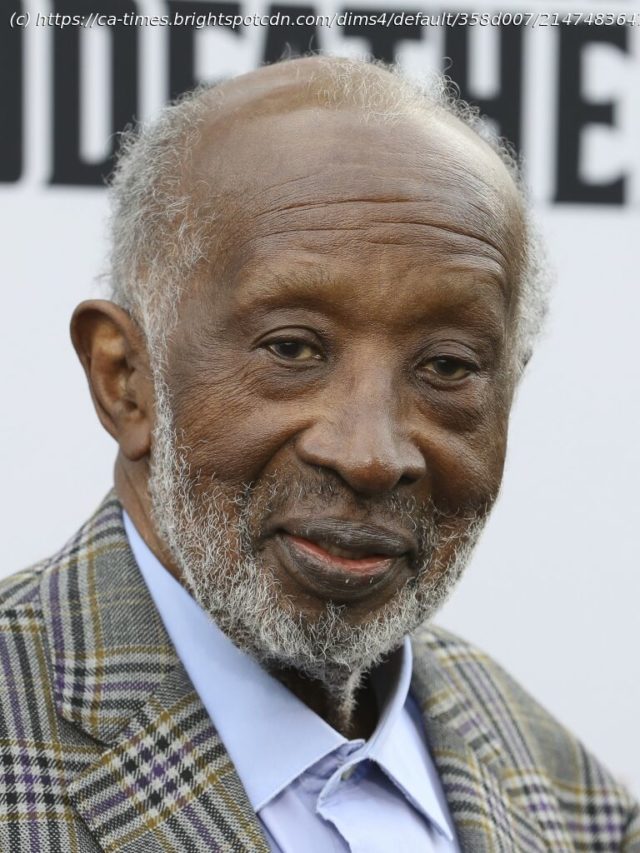

Clarence Avant was a behind-the-scenes titan of managing, deal making and problem solving across the full spectrum of Black entertainment.

Clarence Avant was gruff. He was, by all accounts, foul-mouthed and plain-spoken. But he lived a life that was about opening doors, finding talent, making connections, striking deals, solving problems and getting people the money they were worth.

Avant took care of people — Black people especially but not exclusively — and got them headed in the right direction. And despite working in the music industry, the movie business and politics, he lived his life everywhere but in the spotlight.

A consummate deal closer whose power reached from Hollywood to the White House, Avant “passed away gently at home” on Sunday, according to a Monday statement to The Times from his children, Alex and Nicole Avant, and his son-in-law Ted Sarandos. He was 92.

“Through his revolutionary business leadership, Clarence became affectionately known as ‘The Black Godfather’ in the worlds of music, entertainment, politics, and sports. Clarence leaves behind a loving family and a sea of friends and associates that have changed the world and will continue to change the world for generations to come. The joy of his legacy eases the sorrow of our loss,” the statement said.

Avant died less than two years after his wife, philanthropist Jacqueline Avant, was fatally shot at the longtime couple’s Beverly Hills home.

“[Avant’s] tools are his ability to manipulate people, and I don’t mean that in a bad way,” singer-songwriter Bill Withers — whom Avant discovered and managed — said in “The Black Godfather,” Netflix’s revealing 2019 documentary about Avant’s life. “And if he needs to do it in a bad way, he’s probably good at that too.”

Born in Greensboro, N.C., in 1931 and raised in a nearby town named Climax, Avant was the oldest of eight children. He didn’t really know his birth father and didn’t make it past ninth grade. The Ku Klux Klan was all around, as were his mother’s warnings about how to stay safe.

“We were poor, man. I’m talking about poor, poor, poor,” he said. His nickname was Sweet Potato because that’s what he brought in his school lunch each day instead of a sandwich.

They were humble beginnings for a man who would later go on to sleep in the Lincoln Bedroom in the White House after helping Bill Clinton become president, fully established as a behind-the-scenes titan of managing, deal making and problem solving across the full spectrum of Black entertainment.

A serious clash with his violent stepfather when he was a young teen prompted Avant to move to New Jersey to live with an aunt who had been the first in the family to move north. He never looked back.

He got an office job in New York City, but by 1959 was managing Teddy P’s Lounge in Newark, N.J., a city then filled with jazz clubs. At one of them, he met talent manager Joseph G. Glaser, founder of the Associated Booking Co. and Louis Armstrong’s longtime manager. Avant learned the music business from Glaser, who was alleged to have ties to the organized crime figures behind much of the post-Prohibition nightclub scene.

“I don’t ask Mr. Glaser questions,” Avant said in Netflix’s documentary. “I just learn.”

He was pushed to be an agent but chose to be a manager instead, eventually taking on clients such as R&B singer Little Willie John, jazz singers Sarah Vaughan and Dinah Washington, jazz organist Jimmy Smith and Argentine pianist-composer Lalo Schifrin, who played with Dizzy Gillespie.

He used his contacts in the jazz clubs to impress Jacqueline Gray, a model from Queens, N.Y.

Clarence wooed Jacquie with limo rides and entry to New York clubs such as Birdland and the Apollo Theater, and in 1967 when they got married, she became Jacqueline Avant. The couple raised two children and would remain together for 54 years, until her violent death in an apparent home invasion robbery.

Домой

United States

USA — Science Clarence Avant, the ‘Black Godfather’ of the recording industry, dies at 92