Clouds are a lot cooler than you might think. In fact, scientists might say they’re super cool because they’re made up of millions of supercooled water droplets, droplets that have been cooled below the freezing point but haven’t yet turned into ice. When these droplets freeze, they can accelerate freezing of the whole cloud through a process called secondary ice production. This is a rapid, complex process that happens across different time and length scales.

Clouds are a lot cooler than you might think. In fact, scientists might say they’re super cool because they’re made up of millions of supercooled water droplets, droplets that have been cooled below the freezing point but haven’t yet turned into ice. When these droplets freeze, they can accelerate freezing of the whole cloud through a process called secondary ice production. This is a rapid, complex process that happens across different time and length scales.

«Researchers in the atmospheric science community are trying to understand how ice is being produced so efficiently in clouds, and also what type of ice forms,» said Claudiu Stan, a scientist at Rutgers University. «When ice forms in supercooled water, the water is going to freeze much faster than if you were waiting for ice to form in a freezer. And what people have seen before is you don’t get the same kind of ice that you get from the freezer. But until now, it’s been quite difficult to see what is happening at the very beginning of freezing.»

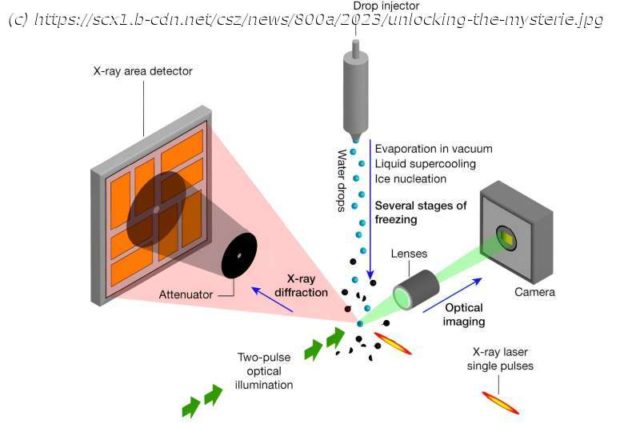

A team of researchers has been exploring this intricate process more closely using the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) X-ray laser, located at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The researchers developed a model of the freezing process that includes seven distinct stages and discovered an unexpected structure along the way. Their results, published today in Nature, could improve our understanding of cloud behavior and its effect on the climate.

«The freezing of these tiny droplets is a phenomenon that isn’t fully understood, and it might contain clues that could help us better understand climate change,» said Stan, who led the study.