The rise of artificial intelligence has sparked a panic about computers gaining power over humankind. But the real threat comes from falling for the hype

In Arthur C Clarke’s short story The Nine Billion Names of God, a sect of monks in Tibet believes humanity has a divinely inspired purpose: inscribing all the various names of God. Once the list was complete, they thought, he would bring the universe to an end. Having worked at it by hand for centuries, the monks decide to employ some modern technology. Two sceptical engineers arrive in the Himalayas, powerful computers in tow. Instead of 15,000 years to write out all the permutations of God’s name, the job gets done in three months. As the engineers ride ponies down the mountainside, Clarke’s tale ends with one of literature’s most economical final lines: “Overhead, without any fuss, the stars were going out.”

It is an image of the computer as a shortcut to objectivity or ultimate meaning – which also happens to be, at least part of, what now animates the fascination with artificial intelligence. Though the technologies that underpin AI have existed for some time, it’s only since late 2022, with the emergence of OpenAI’s ChatGPT, that the technology that approached intelligence appeared to be much closer. In a 2023 report by Microsoft Canada, president Chris Barry proclaimed that “the era of AI is here, ushering in a transformative wave with potential to touch every facet of our lives”, and that “it is not just a technological advancement; it is a societal shift”. That is among the more level-headed reactions. Artists and writers are panicking that they will be made obsolete, governments are scrambling to catch up and regulate, and academics are debating furiously.

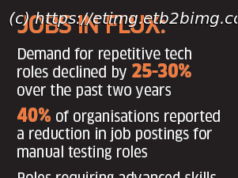

Businesses have been eager to rush aboard the hype train. Some of the world’s largest companies, including Microsoft, Meta and Alphabet, are throwing their full weight behind AI. On top of the billions spent by big tech, funding for AI startups hit nearly $50bn in 2023. At an event at Stanford University in April, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said he didn’t really care if the company spent $50bn a year on AI. Part of his vision is for a kind of super-assistant, one that would be a “super-competent colleague that knows absolutely everything about my whole life, every email, every conversation I’ve ever had, but doesn’t feel like an extension”.

But there is also a profound belief that AI represents a threat. The philosopher Nick Bostrom is among the most prominent voices asserting that AI poses an existential risk. As he laid out in his 2014 book Superintelligence, if “we build machine brains that surpass human brains in general intelligence … the fate of our species would depend on the actions of the machine super-intelligence.” The classic cautionary tale here is that of an AI system whose only – seemingly inoffensive – goal is making paperclips. According to Bostrom, the system would realise quickly that humans are a barrier to this task, because they might switch off the machine. They might also use up the resources needed for the manufacturing of more paperclips. This is an example of what AI doomers call the “control problem”: the fear that we will lose control of AI because any defences we’ve built into it will be undone by an intelligence that’s millions of steps ahead of us.

Before we do, in fact, cede any more ground to our tech overlords, it’s worth casting your mind back to the mid-1990s and the arrival of the world wide web. That, too, came with profound assertions of a new utopia, a connected world in which borders, difference and privation would end. Today, you would be hard pressed to argue that the internet has been some sort of unproblematic good. The fanciful did come true; we can carry the whole world’s knowledge in our pockets. This just had the rather strange effect of driving people a bit mad, fostering discontent and polarisation, assisting a renewed surge of the far right and destabilising democracy and truth.

It’s not that you should simply resist technology; it can, after all, also have liberating effects. Rather, when big tech comes bearing gifts, you should probably look closely at what’s in the box.

What we call AI at the moment is predominantly focused on large language models, or LLMs. The models are fed massive sets of data – ChatGPT essentially hoovered up the entire public internet – and trained to find patterns in them. Units of meaning, such as words, parts of words and characters, become tokens and are assigned numerical values. The models learn how tokens relate to other tokens and, over time, learn something like context: where a word might appear, in what order, and so on.

That doesn’t sound impressive on its own. But when I recently asked ChatGPT to write a story about a sentient cloud who was sad the sun was out, the results were strikingly human. Not only did the chatbot produce the various components of a children’s fable, it also included a story arc in which, eventually, “Nimbus” the cloud found a corner of the sky and made peace with a sunny day. You might not call the story good, but it would probably entertain my five-year-old nephew.

Robin Zebrowski, professor and chair of cognitive science at Beloit College in Wisconsin, explains the humanity I sensed this way: “The only truly linguistic things we’ve ever encountered are things that have minds. And so when we encounter something that looks like it’s doing language the way we do language, all of our priors get pulled in, and we think: ‘Oh, this is clearly a minded thing.’”

This is why, for decades, the standard test for whether technology was approaching intelligence was the Turing test, named after its creator Alan Turing, the British mathematician and second world war code-breaker. The test involves a human interrogator who poses questions to two unseen subjects – a computer and another human – via text-based messages to determine which is the machine. A number of different people play the roles of interrogator and respondent, and if a sufficient proportion of interviewers is fooled, the machine could be said to exhibit intelligence. ChatGPT can already fool at least some people in some situations.

Such tests reveal how closely tied to language our notions of intelligence are. We tend to think that beings that can “do language” are intelligent: we marvel at dogs that appear to understand more complex commands, or gorillas that can communicate in sign language, precisely because such acts are closer to our mechanism of rendering the world sensible.

But being able to do language without also thinking, feeling, willing or being is probably why writing done by AI chatbots is so lifeless and generic. Because LLMs are essentially looking at massive sets of patterns of data and parsing how they relate to one another, they can often spit out perfectly reasonable-sounding statements that are wrong or nonsensical or just weird. That reduction of language to just collection of data is also why, for example, when I asked ChatGPT to write a bio for me, it told me I was born in India, went to Carleton University and had a degree in journalism – about which it was wrong on all three counts (it was the UK, York University and English). To ChatGPT, it was the shape of the answer, expressed confidently, that was more important than the content, the right pattern mattering more than the right response.

All the same, the idea of LLMs as repositories of meaning that are then recombined does align with some assertions from 20th-century philosophy about the way humans think, experience the world, and create art. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida, building on the work of linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, suggested that meaning was differential – the meaning of each word depends on that of other words. Think of a dictionary: the meaning of words can only ever be explained by other words, which in turn can only ever be explained by other words. What is always missing is some sort of “objective” meaning outside this neverending chain of signification that brings it to a halt. We are instead forever stuck in this loop of difference. Some, like Russian literary scholar Vladimir Propp, theorised that you could break down folklore narratives into constituent structural elements, as per his seminal work, Morphology of the Folktale. Of course, this doesn’t apply to all narratives, but you can see how you might combine units of a story – a starting action, a crisis, a resolution and so on – to then create a story about a sentient cloud.