It’s a sunny June day in southeast England. I’m driving along a quiet, rural road that stretches through the Kent countryside. The sun flashes through breaks in the hedgerow, offering glimpses of verdant crop fields and old .

It’s a sunny June day in southeast England. I’m driving along a quiet, rural road that stretches through the Kent countryside. The sun flashes through breaks in the hedgerow, offering glimpses of verdant crop fields and old farmhouses.

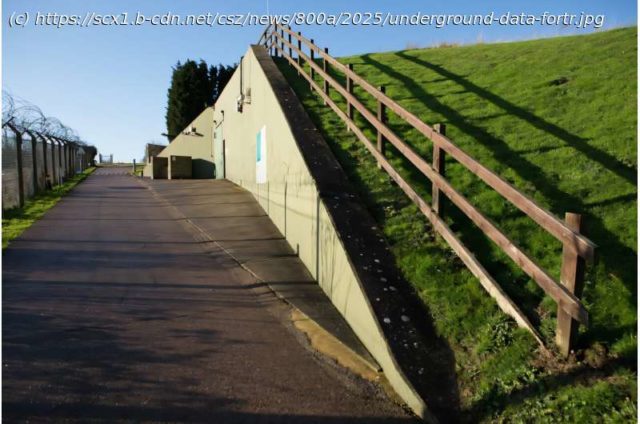

Thick hawthorn and brambles make it difficult to see the 10ft-high razor-wire fence that encloses a large grassy mound. You’d never suspect that 100ft beneath the ground, a hi-tech cloud computing facility is whirring away, guarding the most valuable commodity of our age: digital data.

This subterranean data center is located in a former nuclear bunker that was constructed in the early 1950s as a command-and-control center for the Royal Air Force’s radar network. You can still see the decaying concrete plinths that the radar dish once sat upon. Personnel stationed in the bunker would have closely watched their screens for signs of nuclear missile-carrying aircraft.

After the end of the cold war, the bunker was purchased by a London-based internet security firm for use as an ultra-secure data center. Today, the site is operated by the Cyberfort Group, a cybersecurity services provider.

I’m an anthropologist visiting the Cyberfort bunker as part of my ethnographic research exploring practices of «extreme» data storage. My work focuses on anxieties of data loss and the effort we take—or often forget to take—to back-up our data.

As an object of anthropological inquiry, the bunkered data center continues the ancient human practice of storing precious relics in underground sites, like the tumuli and burial mounds of our ancestors, where tools, silver, gold and other treasures were interred.

The Cyberfort facility is one of many bunkers around the world that have now been repurposed as cloud storage spaces. Former bomb shelters in China, derelict Soviet command-and-control centers in Kyiv and abandoned Department of Defense bunkers across the United States have all been repackaged over the last two decades as «future-proof» data storage sites.

I’ve managed to secure permission to visit some of these high-security sites as part of my fieldwork, including Pionen, a former defense shelter in Stockholm, Sweden, which has attracted considerable media interest over the last two decades because it looks like the hi-tech lair of a James Bond villain.

Many abandoned mines and mountain caverns have also been re-engineered as digital data repositories, such as the Mount10 AG complex, which brands itself as the «Swiss Fort Knox» and has buried its operations within the Swiss Alps.

Cold war-era information management company Iron Mountain operates an underground data center 10 minutes from downtown Kansas City and another in a former limestone mine in Boyers, Pennsylvania.

The National Library of Norway stores its digital databanks in mountain vaults just south of the Arctic Circle, while a Svalbard coal mine was transformed into a data storage site by the data preservation company Piql. Known as the Arctic World Archive (AWA), this subterranean data preservation facility is modeled on the nearby Global Seed Vault.

Just as the seeds preserved in the Global Seed Vault promise to help re-build biodiversity in the aftermath of future collapse, the digitized records stored in the AWA promise to help re-boot organizations after their collapse.

Bunkers are architectural reflections of cultural anxieties. If nuclear bunkers once mirrored existential fears about atomic warfare, then today’s data bunkers speak to the emergence of a new existential threat endemic to digital society: the terrifying prospect of data loss.Data, the new gold?

After parking my car, I show my ID to a large and muscular bald-headed guard squeezed into a security booth not much larger than a payphone box. He’s wearing a black fleece with «Cyberfort» embroidered on the left side of the chest. He checks my name against today’s visitor list, nods, then pushes a button to retract the electric gates.

I follow an open-air corridor constructed from steel grating to the door of the reception building and press a buzzer. The door opens on to the reception area: «Welcome to Cyberfort», receptionist Laura Harper says cheerfully, sitting behind a desk in front of a bulletproof window which faces the car park. I hand her my passport, place my bag in one of the lockers, and take a seat in the waiting area.

Big-tech pundits have heralded data as the «new gold»—a metaphor made all the more vivid when data is stored in abandoned mines. And as the purported economic and cultural value of data continues to grow, so too does the impact of data loss.

For individuals, the loss of digital data can be a devastating experience. If a personal device should crash or be hacked or stolen with no recent back-ups having been made, it can mean the loss of valuable work or cherished memories. Most of us probably have a data-loss horror story we could tell.

For governments, corporations and businesses, a severe data loss event—whether through theft, erasure or network failure—can have a significant impact on operations or even result in their collapse. The online services of high-profile companies like Jaguar and Marks & Spencer have recently been impacted by large-scale cyber-attacks that have left them struggling to operate, with systems shutdown and supply chains disrupted.

But these companies have been comparatively lucky: a number of organizations had to permanently close down after major data loss events, such as the TravelEx ransomware attack in 2020, and the MediSecure and National Public Data breaches, both in 2024.

With the economic and societal impact of data loss growing, some businesses are turning to bunkers with the hope of avoiding a data loss doomsday scenario.The concrete cloud

One of the first things visitors to the Cyberfort bunker encounter in the waiting area is a 3ft cylinder of concrete inside a glass display cabinet, showcasing the thickness of the data center’s walls. The brute materiality of the bunkered data center stands in stark contrast to the fluffy metaphor of the «cloud», which is often used to discuss online data storage.

Data centers, sometimes known as «server farms», are the buildings where cloud data is stored. When we transfer our data into the cloud, we are transferring it on to servers in a data center (hence the meme «there is no cloud, just someone else’s computer»).

Data centers typically take the form of windowless, warehouse-scale buildings containing hundreds of servers (pizza box-shaped computers) stored in cabinets that are arranged in aisles.

Data centers are responsible for running many of the services that underpin the systems we interact with every day. Transportation, logistics, energy, finance, national security, health systems and other lifeline services all rely on up-to-the-second data stored in and accessed through data centers.

Everyday activities such as debit and credit card payments, sending emails, booking tickets, receiving text messages, using social media, search engines and AI chatbots, streaming TV, making video calls and storing digital photos all rely on data centers.

These buildings now connect such an incredible range of activities and utilities across government, business and society that any downtime can have major consequences. The UK government has officially classified data centers as forming part of the country’s critical national infrastructure—a move that also conveniently enables the government to justify building many more of these energy-guzzling facilities.

Домой

United States

USA — software Underground data fortresses: The nuclear bunkers, mines and mountains being transformed to...